Program Evaluation of the Broadening Access to Second Language Learning Products Through Canadian Universities Project

Final report

July 2012

Prepared for: Canada School of Public Service

Prepared by: R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd.

Table of contents

Executive summary

To fulfil its obligations under Section 41 of the Official Languages Act, the Government of Canada created the Official Languages Branch of Intergovernmental Affairs in 2003, and instituted the 2003-2008 Action Plan for Official Languages. As the Action Plan was coming to its planned end in 2008, the Government of Canada developed the Roadmap for Canada's Linguistic Duality 2008-2013: Acting for the Future. The Roadmap is a government-wide investment of $1.1 billion over five years that encourages the participation of all Canadians in linguistic duality and supports official

language minority communities.Footnotes1

In 2009, under the Roadmap, the Canada School of Public Service (the School) launched a three-year pilot initiative, the Broadening Access to Second Language Learning Products through Canadian Universities Project, to broaden access to the School's online second language maintenance and acquisition tools by making them accessible to students at Canadian universities. Ultimately, this project was designed to help renew the public service by helping to draw in qualified and competent workers that meet the current and future bilingual workforce requirements of the Government of Canada.

Evaluation method

The Universities Project concluded in March 2012. This evaluation will help the School to determine whether the Universities Project has remained relevant and has been effective at achieving its objectives.

Three lines of evidence were used to inform this evaluation: a document review; key informant interviews with employees and management at the School, along with university coordinators; and online surveys of project participants, including surveys previously administered by the School.

Evaluation findings

Overall, findings from this evaluation suggest that the Universities Project has the potential to contribute to the renewal of a bilingual federal public service and to increase the understanding of the importance of linguistic duality in Canada. Although the extent to which the project achieved expected outcomes was limited owing to unforeseen technical issues and challenges to participant engagement, learning from the current project could help establish cost-effective approaches to addressing these two government priorities in the future.

Need and relevance

Data collected and analysed for this evaluation confirmed the need for opportunities for youth to learn and maintain their second language, as well as the relevance of such an initiative within the federal government.

Firstly, while more Canadians between the ages of 10 and 29 know both official languages, compared to the entire population, Census data indicate that this trend may be ebbing as the gap between youth and older age groups has decreased in the years 2001 to 2006.

A decrease in bilingualism among Canadian youth will impact the Canadian public service. While efforts to recruit and retain new staff over the past few years have been successful, the projected retirement rate for the next three years is 3.4%, representing the highest rate since 2005.Footnotes2 For the federal government to maintain the delivery of excellent services, efforts to enhance public service renewal will be crucial.

Performance of the Universities Project

Participants and coordinators were satisfied with the learning tools and services provided through the Universities Project. The most unique and attractive feature of the project was the opportunity for participants to take the Public Service Commission's second language test that created a government-recognized language profile.

Technical difficulties were identified as a significant challenge impeding participants' effective access to the learning tools. Participants' frustration with the technical difficulties likely contributed to reduced participation and high level of withdrawal from the project. Many more likely discontinued their participation, but did not withdraw formally.

However, the data suggest that for those who did continue with the project, many realized significant gains in their linguistic abilities. A comparison between project participants' scores in the second language tests at the beginning of the project and again at the end indicates improvement in second language skills for those who actively participated in the project.

Efficiency and economy of the Universities Project

Online delivery has the potential to be a cost-effective approach to providing language skills development. Now that the development and implementation phases are complete, costs of continued project delivery would decrease.

Section 1: Project background

1.1 Context

Under section 41 of the Official Languages Act, the Government of Canada is committed to enhancing the vitality of the English and French languages in Canada, supporting and assisting in their development, and fostering the recognition and use of both official languages in Canadian society. The government's objectives in this regard include ensuring respect for and equality of the status of the two official languages in federal institutions, particularly with regard to the provision of services to the public.Footnotes3

1.1.1 The Government of Canada's approach to bilingualism

As part of its dedication to bilingualism, the federal government created the Official Languages Branch of Intergovernmental Affairs in 2003 (this agency has since joined the Department of Canadian Heritage), and appointed the first-ever minister responsible for official languages. In addition, the federal government instituted the 2003-2008 Action Plan for Official Languages. The Action Plan was a five-year policy statement stemming from the Official Languages Act and contained specific initiatives intended to strengthen and promote linguistic duality. Through the Action Plan, the federal government sought to focus government resources and support on three priority areas: education, community development, and exemplary public service delivery.Footnotes4

The Government of Canada consulted key stakeholders such as official language minority communities, parliamentary committees and the Commissioner of Official Languages, in developing the Roadmap for Canada's Linguistic Duality 2008-2013: Acting for the Future. The Roadmap is a government-wide investment of $1.1 billion over five years. The Roadmap now represents the Government of Canada's official languages strategy and serves to outline the government's major policy directions.

1.1.2 The role of the Canada School of Public Service

Created in April 2004, the Canada School of Public Service (the School) provides learning opportunities to members of the public service with the objective of developing a learning culture within the federal government, and improving the services provided to Canadians.

The School's mandate is to facilitate the following:Footnotes5

- Encourage pride and excellence in the public service;

- Foster a common sense of purpose, values and traditions in the public service;

- Support deputy heads in meeting the learning needs of their organizations; and

- Pursue excellence in public management and administration.

The School provides the development required for public servants to perform in a bilingual environment through the provision of learning opportunities. Four initiatives support this program activity:

- Required training — includes orientation to the public service and training in authority delegation;

- Professional development training — includes professional development and programming that supports functional linguistic communities;

- Official languages learning — includes access to language training and maintenance; and

- Online learning — includes online courses and collaborative technologies.Footnotes6

With this mandate and these initiatives in mind, it was determined that the School would play an active role in supporting the Roadmap's call to emphasize the value of linguistic duality, to invest in youth, and to improve access to services in both languages.

1.1.3 The Canadian Universities Project

In 2009, the School launched the Broadening Access to Second Language Learning Products through Canadian Universities Project (herein referred to as the Universities Project), a three-year pilot initiative to provide students of selected Canadian universities with access to its online, self-paced official language maintenance and acquisition tools.

Through this project, the School aimed to facilitate closing the gap between current second language levels acquired by university students and those required when joining the federal public service. In doing so, this project was designed to help renew the public service by helping to draw in qualified and competent workers that meet the current and future bilingual requirements of the Government of Canada. In addition, the project was intended to foster an increased understanding of Canada's linguistic duality.

The School invited 36 universities to submit an application for participation in the Universities Project. In their applications, universities were required to demonstrate their capacity and commitment to the project by confirming the following:

- Commitment to take part actively in the initiative for the three years;

- Commitment to provide at least one bilingual resource to the initiative for three years;

- Commitment (in collaboration with the School) to promote and facilitate second language learning and use of both official languages;

- Commitment to choose and maintain a minimum of ten students in the initiative for three years;

- Willingness to work with the School in providing access to products available in the learning management system;

- Desire to work in partnership and collaboration with other universities;

- Capacity to show innovation and creativity in accessing current and new learning products and activities;

- Interest in promoting second language learning and bilingualism; and

- Choosing to be part of a consortium (i.e. forming an association to reach common objectives and complete a certain number of activities).

In particular, universities were responsible for recruiting project participants and providing support for their learning through various activities and more importantly, by providing them with opportunities to practice their oral skills in their second official language. Typically, universities designated one staff member to coordinate and implement these activities. In a few cases, an outside resource was hired to coordinate the Universities Project within the university. The School's staff and university coordinators communicated as needed. Also, regular teleconferences were organized to discuss issues and provide formal updates to all university coordinators.

Of the targeted universities, 13 submitted an application. Based on an evaluation of the submissions, the School selected 11 universities with which to sign a memorandum of understanding. In March 2010, the University of Toronto (Scarborough Campus) withdrew from the project after the school realized it could not provide the necessary supports to participating students. 10 universities participated in the project.

The selected universities were responsible for project participant recruitment and the methods selected to inform and encourage students to participate varied across institutions. Some universities targeted a certain student demographic or those in a certain field of study. Others opened the invitation up to all students. The approaches used included providing information in marketing materials at the beginning of the academic year, presenting the project to specific classes such as ESL or FSL courses, and organizing information sessions for interested students.

The project provided the opportunity for its participants to learn either French or English as a second language and consisted of a core program along with a number of complementary learning tools. For French learners, the online version of a program designed for the public service (PFL2AB) was modified for university students. For English learners, a commercial product called Tell Me More was selected.

Through the Universities Project, the School also endeavoured to create an online community around linguistic duality and facilitate dialogue among project participants by hosting blogs and discussion forums and creating a Facebook page. A meeting with the Commissioner of Official Languages was also organized to educate participants and discuss issues around linguistic duality. This meeting was attended in person and by videoconference.

The project offered two learning approaches: guided and self-directed. Self-directed students were provided access to all tools and were left to pursue their learning on their own. Guided learners were also provided access to the online tools, but were also sent weekly bulletins to support their learning. Bulletins guided participants by highlighting the main learning objectives and suggesting activities to explore, apply and integrate newly developed language skills as well as providing additional information to support learning.

Universities were able to choose which learning approach (self-directed or guided) they wished to offer their students. Table 1-1 provides the number of participants enrolled in each of the learning options at the beginning of the project.

Table 1-1: Participants of Universities Project

Table 1-1 provides the number of participants enrolled in each of the learning options at the beginning of the project. The first column contains the name of the participating universities. The second column contains the total enrolment in the program. The third and the fourth columns contain the number of French guided and French self-directed participants respectively. The fifth and sixth columns contain the number of English guided and English self-directed participants respectively. The seventh column contains the number of participants for which the learning approach is unknown. The last column regroups the specific data for the control group which are not included in the total enrolment.

| |

Total

Enrolment |

French

Guided |

French

Self-

Directed |

English

Guided |

English

Self-

Directed |

Unknown

ApproachFootnotes* |

Control

GroupFootnotes** |

| Carleton University |

27 |

27 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

| École national d'administration publique |

29 |

- |

- |

- |

29 |

- |

4 |

| York University – Glendon Campus |

29 |

29 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Université Sainte-Anne |

18 |

- |

13 |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

| Simon Fraser University |

32 |

14 |

14 |

- |

- |

4 |

4 |

| University of Alberta |

14 |

14 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

| University of Ottawa |

37 |

18 |

3 |

11 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

| University of Regina |

36 |

36 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| University of Waterloo |

29 |

29 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| University of Victoria |

31 |

- |

31 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Total |

282 |

167 |

61 |

11 |

38 |

5 |

21 |

To measure the level of their skill development, participants were provided the opportunity to take the Public Service Commission's second language test at the beginning and again at the end of the project. The project also included a control group of students from participating universities who did not have access to the online tools, but could complete the second language test at the beginning and end of the project.

1.2 Purpose of the evaluation

The Universities Project concluded in March 2012. This evaluation will help the School to determine whether the Universities Project has remained relevant to government priorities and has been effective at achieving its objectives.

The evaluation was conducted in the context of the Results-based Management Accountability Framework developed by the School for the project at its inception. In accordance with this overarching framework, the evaluation questions discussed are related to the following issues:

- Relevance:

- Continued need for the project;

- Alignment with government priorities; and

- Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities.

- Performance:

- Effectiveness: development of students' second language skills to levels required to work in the public service;

- Efficiency: overall quantity, quality, and blend of learning products to encourage second-language development; and

- Economy: effective management of resources to facilitate the achievement of relevant outcomes.

The matrix developed for this evaluation, containing all questions, indicators and measures, is included in Appendix A.

Section 2: Evaluation methodology

The three lines of evidence used for the evaluation of the Universities Project were:

- a document review;

- key informant interviews; and

- surveys of project participants.

Data from the various lines of evidence were analysed with respect to answering the evaluation questions.

2.1 Document review

The Consultant reviewed administrative documents, annual financial reports and previously collected performance data.

- The review of administrative documentation primarily focused on extracting information to assess the core issues associated with relevance; that is, the extent to which the Universities Project is aligned to federal and departmental priorities.

- The review of the previously collected performance data, including the before and after government-recognized second language tests, will be used as part of the assessment of the extent to which the project is achieving its objectives, as well as the extent to which it is being delivered efficiently and economically.

- Program budget information was used as part of an assessment of the project's efficiency and economy.

2.2 Key informant interviews

The Consultant conducted a total of 14 key informant interviews with project coordinators from participating universities, as well as project staff and management at the School (Table 2-1).

Table 2-1: Completed Key Informant Interviews

The table shows the number of completed key informant interviews. The first column contains the informant types. The second column contains the number of interviews.

| Informant Type |

Number of Interviews |

| University Coordinator |

8 |

| The School's Program Staff |

3 |

| The School's Program Management |

3 |

| Total |

14 |

Key informant interviews served to inform the evaluation in the areas of relevance and performance, as well as support information collected through other lines of evidence.

The Consultant developed a semi-structured interview guide for the key informant interviews. The guide contained a core set of questions for the three informant types (i.e. university coordinators, the School's staff and the School's management); however, some specific questions were also included for each group, reflecting their different roles and experiences. (The key informant interview guide is included as Appendix B.)

An introduction letter was drafted by the School and sent to potential key informants via e-mail prior to scheduling interviews. The letter provided information about the evaluation, introduced the Consultant and explained the purpose of the interviews.

The interview scheduling process included providing the interview guide to all key informants prior to their interview to allow time for review and preparation. Afterwards, key informants were sent the notes taken during their interviews for validation. Information was then entered into an interview database to facilitate analysis.

2.3 Surveys of project participants

To evaluate the performance of the Universities Project, participants were contacted to record their motivations for participating; their perceptions of the tools and supports; and the impact that the project has had on their ability to communicate in their second official language. The School administered a series of questionnaires during the project to ensure it was on course and to better understand the participants. The final questionnaire was administered by R.A. Malatest & Associates and sought to answer evaluation questions not covered by the previous surveys and record participants' overall perceptions of the project.

2.3.1 Previous surveys of participants

Participants had been invited to complete motivation and satisfaction surveys at various points throughout the project. However, no single iteration of the surveys contained data from a large proportion of participants. To soundly analyze data collected through these earlier surveys, the Consultant merged the data files from the various iterations, purging cases where participants had answered the questionnaire at multiple points in time (keeping the most recent record). In total, information from 134 participant motivation surveys was compiled into a single database. The database for the satisfaction survey contained 39 records from those who had participated in self-directed learning and 37 records from those who had participated in guided learning (the satisfaction survey was slightly different for self-directed and guided participants).

2.3.2 Final online survey of participants

The Consultant developed a final participant questionnaire suitable for online self-administration with an approximate length of 5 to 10 minutes. The Consultant designed the questionnaire by comparing the information provided from the previous satisfaction and motivation surveys to the information required in the evaluation matrix. Those areas of interest that had not been adequately covered were identified for inclusion for the final participant survey. The final questionnaire was also designed to provide participants with the opportunity to provide feedback on their overall experience with the project. (The final online survey questionnaire is included as Appendix C.)

The final questionnaire included questions that covered:

- Level of participation in the project;

- Reasons for withdrawing from the project;

- Access to coordinators and other supports;

- The project compared to other online and language development resources;

- Change in confidence of communicating in the other official language;

- Interest in the public service as a career; and

- The perceived importance of linguistic duality.

All participants in the project were invited to complete the final survey. The names of 302 participants were compiled into a single database, including 21 from the control group. The survey was timed to occur before, during and after the first term exam period (November through January) to allow participants to find a suitable time to respond.

The survey was sent to participants via e-mail introducing the survey and providing a secure, unique link to the online questionnaire. As a trial, 40 participants were invited to complete the questionnaire on November 24, 2011, to ensure that the questionnaire was working as intended, the wording was understood and the length was appropriate.

After confirming that no issues were reported by the trial group, the remaining participants were sent the e-mail invitation on November 29, 2011. Full survey administration ran until January 13, 2012. To facilitate a higher response rate, the Consultant sent e-mail reminders to those that had not yet responded on December 5, 12 and 19, 2011.

In total, 82 participants completed the final online survey yielding a gross response rate of 27%. It was decided that responses from the control group would be excluded from the analysis. The final database contains 75 responses with an overall margin of error of ±9.7% at the 95% confidence interval.

Table 2-2 presents the number of completed surveys from each university, the number of male and female respondents, and the numbers of participants who are in undergraduate and graduate programs of study. Note that not all respondents provided demographic information; therefore totals for gender and level of study will not always correspond with the overall number of survey respondents. Response rates varied between universities from a low of 10% to a high of 48% (Table 2-3). There was a lower response rate from the University of Victoria (10%) and the University of Regina (14%).

Table 2-2: Final Online Survey Participation Results (#)

The table presents the final online survey participation results. The first column outlines the names of the participating universities. The second column gives the total number of respondents for each university. The third and fourth columns indicate the number of male and female participants respectively. Finally, the fifth and sixth columns indicate the number of undergraduate and graduate students respectively.

| |

Total

Respondents

n = 75 |

Male

n = 23 |

Female

n = 48 |

Undergraduate

n = 33 |

Graduate

n = 38 |

| Carleton University |

6 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

6 |

| École national d'administration publique |

14 |

8 |

6 |

0 |

13 |

| York University – Glendon Campus |

6 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

| Université Sainte-Anne |

7 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

| Simon Fraser University |

12 |

2 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

| University of Alberta |

3 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| University of Ottawa |

10 |

3 |

7 |

9 |

1 |

| University of Regina |

5 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

| University of Waterloo |

9 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

8 |

| University of Victoria |

3 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

Source: Online survey of participants

Table 2-3: Final Online Survey of Project Participants – Response Rates

Table 2-3 shows the final online survey of project participants' response rates. The first column gives the name of the participating universities. The second column indicates the sample size. The third column contains the number of responses received, while the fourth column gives the response rate.

| |

SampleFootnotes* |

Number of Responses |

Response Rate |

| Carleton University |

27 |

6 |

22% |

| École national d'administration publique |

29 |

14 |

48% |

| York University – Glendon Campus |

29 |

6 |

21% |

| Université Sainte-Anne |

18 |

7 |

39% |

| Simon Fraser University |

32 |

12 |

38% |

| University of Alberta |

14 |

3 |

21% |

| University of Ottawa |

37 |

10 |

27% |

| University of Regina |

36 |

5 |

14% |

| University of Waterloo |

29 |

9 |

31% |

| University of Victoria |

31 |

3 |

10% |

| Total |

282 |

75 |

27% |

At the conclusion of the survey, data were entered into a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) database to produce the final survey results. The results for each question were cross-tabulated by learning approach (self-directed or guided) and language of study (English or French). The results of the final online survey, as well as the previous surveys, will be presented throughout much of the remainder of this report.

Table 2-4: Number of Online Survey Participants by Learning Approach and Language

This table breakdowns the number of online survey participants by learning approach and language. The first column identifies the name of the participating universities. The second column presents the total number of participants in each university. The third and the fourth columns indicate if the participants studied English or French respectively. Finally, the fifth and sixth columns outline the number of participants who were self-directed and guided respectively.

| |

Total |

English |

French |

Self-directed |

Guided |

| Carleton University |

6 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

| École national d'administration publique |

14 |

14 |

0 |

14 |

0 |

| York University – Glendon Campus |

6 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

| Université Sainte-Anne |

7 |

1 |

6 |

7 |

0 |

| Simon Fraser University |

12 |

0 |

12 |

5 |

7 |

| University of Alberta |

3 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

| University of Ottawa |

10 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

8 |

| University of Regina |

5 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

| University of Waterloo |

9 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

| University of Victoria |

3 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

| Total |

75 |

22 |

53 |

31 |

44 |

Source: Online survey of participants

n = 75

2.4 Limitations of the evaluation

The findings of this evaluation are limited by the participants' limited response rates to the various surveys, and by the potential biases associated with those who did complete them. For instance, while all project participants were eligible to complete the final online survey, only 27% were able or willing to provide input. As students have been invited to participate in previous surveys throughout the project, there may have been some fatigue that affected their decision to participate or not in the final survey. In addition, while the Consultant typically conducts telephone reminder calls when administering an online survey to increase response rates, this was not possible for this evaluation. The online survey was limited to those who could be reached via their university e-mail address.

Furthermore, there may have been a respondent bias, as those students who have remained engaged with the project were more likely to respond to communications from the School and complete the surveys. The majority of the final online survey (60%) was completed by respondents from four universities: ENAP (19%), Simon Fraser University (16%), the University of Ottawa (13%) and the University of Waterloo (12%). The University of Victoria and the University of Alberta, with a response proportion of 4%, as well as the University of Regina (7%) were underrepresented in the survey.

This evaluation is also limited by the fact that the impact of the project on language competencies can only be measured among those who completed the standardized language test both at the outset and near the conclusion of their participation. Those who withdrew from the project, or were otherwise unable to complete both tests, are not considered in the analysis.

The report has been written with these limitations in mind. The conclusions have been made where various lines of evidence support each other. However, individual findings in this evaluation should be considered in light of their limitations.

Section 3: Evaluation findings

Findings from this evaluation suggest that the Universities Project has the potential to contribute to the renewal of a bilingual federal public service and enhance the linguistic duality of Canada. There is overall satisfaction with the project and the results from the Public Service Commission's second language tests indicate improvements in participants' language skills. Despite these achievements, the impact that can be attributed to the project has been limited due to unforeseen technical issues and limited participant engagement. The following sections discuss more specifically the findings related to each project evaluation question and the extent to which the expected outcomes of the project were achieved.

3.1 Relevance of the Universities Project

Despite widespread agreement on the importance and benefit of knowing both official languages in Canada, bilingualism among youth has decreased in the last decade.Footnotes7 Students at the primary, secondary and in particular, post-secondary levels require increased support to learn their second official languages as research demonstrates that opportunities to develop these skills are currently limited. Furthermore, for the federal public service to maintain a quality service to Canadians in both official languages, a pool of young bilingual recruits is necessary.

3.1.1 The current need for an initiative such as the Universities Project

Need to increase proficiency in second official language

While most Canadians are in favour of bilingualism in Canada (72%),Footnotes8 few have learned their second official language. Statistics Canada data suggest that only 17% of Canadians know both official languages (Table 3-1) with the majority of bilingual Canadians residing in Quebec and Ontario.

Census 2006 data do suggest that bilingualism is more common among younger Canadians, including university-aged youth (23.4% of Canadians aged 20-24 indicated that they were bilingual, versus 17.4% of the Canadian population as a whole). However this level of bilingualism among university-aged youth represents a significant decrease from just five years earlier (when 26.2% of 20-24 years olds were bilingual).Footnotes9 This decline has occurred despite a 10% increase in enrolment in French second language immersion programs within elementary and secondary schools since 2000-2001.Footnotes10 This finding may suggest that Canadian students, particularly university students, need more direct and continuing help to fully develop or maintain their official language skills.

Table 3-1: Canadians with Knowledge of French and English by Province/Territory

Table 3-1 shows how many Canadians possess knowledge of French and English by provinces and territories. The first column identifies the Canadian provinces and territories. The second column represents the number of individuals with the knowledge of French and English. The third column gives the total population of the provinces and territories. The fourth column shows which proportions of the provincial and territorial populations are bilingual, while the fifth column shows what the proportions represent vis-à-vis the entire Canadian population.

| |

Knowledge of

FR and EN |

Total

Population |

Proportion

in Province |

Proportion

in Canada |

| Quebec |

3,017,860 |

7,435,905 |

40.6% |

55.4% |

| Ontario |

1,377,325 |

12,028,895 |

11.5% |

25.3% |

| British Columbia |

295,645 |

4,074,385 |

7.3% |

5.4% |

| New Brunswick |

240,085 |

719,650 |

33.4% |

4.4% |

| Alberta |

222,885 |

3,256,355 |

6.8% |

4.1% |

| Manitoba |

103,520 |

1,133,510 |

9.1% |

1.9% |

| Nova Scotia |

95,010 |

903,090 |

10.5% |

1.7% |

| Saskatchewan |

47,450 |

953,850 |

5.0% |

0.9% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador |

23,675 |

500,610 |

4.7% |

0.4% |

| Prince Edward Island |

17,100 |

134,205 |

12.7% |

0.3% |

| Northwest Territories |

3,665 |

41,055 |

8.9% |

0.1% |

| Yukon |

3,440 |

30,195 |

11.4% |

0.1% |

| Nunavut |

1,170 |

29,325 |

4.0% |

<0.1% |

| Canada |

5,448,850 |

31,241,030 |

17.4% |

100% |

Source: Census 2006 data. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo15-eng.htm

However, few second language development opportunities are available for university students. When entering post-secondary studies, research indicates that there may be a lack of support or incentive for students to learn their second official language. For example, a study conducted by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL) in 2009 found that a low proportion of post-secondary institutions required their students to know the other official language when they enrolled or when they graduated. Another study conducted by the OCOL in 2008 found that while most Canadian post-secondary institutions have adopted measures to promote learning French or English as a second language, the availability of ESL and FSL courses was generally quite limited. Also, only 22% of English language institutions and 50% of French language institutions provided their students with the opportunity to take courses in their field of study in their second language.Footnotes11

The federal government should be concerned about the current lack of bilingualism among university students because fewer graduates can be recruited into the public service in jobs offering bilingual services to the Canadian public.

Need to renew a bilingual public service

While efforts to recruit and retain younger employees over the past few years have been successful, half of the public service is over the age of 45 and the proportion aged 55 and over has increased since 2005. Accordingly, the projected retirement rate for the next three years is 3.4%, the highest rate since 2005.Footnotes12

For the federal public service to maintain the delivery of excellent public services, efforts that support public service renewal will be crucial.Footnotes13

Because of the federal government's commitment to providing services in both official languages, ensuring bilingualism among public service recruits will be high priority for its renewal. While not all public service employees are required to be bilingual, depending on the duties and responsibilities of the position, approximately 41% of jobs in the federal public service are designated bilingual. The greatest concentration of bilingual positions is in the National Capital Region (65.4%), Quebec (64.9%) and New Brunswick (52.7%).Footnotes14 In recent years, the federal government, through the Public Service Commission, has increased efforts to ensure that individuals occupying bilingual positions do in fact possess the necessary language proficiencies. As a result, the proportion of non-imperative appointmentsFootnotes15 has decreased from 11% in 2006-2007 to 6.3% in 2009-2010.Footnotes16 While this signifies that bilingual positions being posted are increasingly filled by bilingual candidates, the proportion of public servants who did not meet the language requirements of their position at the time of their appointment remains at 14% in 2009-2010 as it did in 2006-2007.Footnotes17 Continuing to fill bilingual positions with bilingual employees will decrease this proportion over time, further ensuring the provision of federal services in both official languages.

3.1.2 The Universities Project is addressing government priorities and the School's priorities

To evaluate whether the Universities Project is consistent with the Government of Canada's commitment to language duality, the Universities Project was assessed against two key policy documents: Roadmap for Canada's Linguistic Duality 2008-2013 and the Official Languages Act. Roadmap for Canada's Linguistic Duality 2008-2013 outlines five areas for action:

- Emphasizing the value of linguistic duality among all Canadians;

- Building the future by investing in youth;

- Improving access to services for official languages minority communities;

- Capitalizing on economic benefits; and

- Ensuring efficient governance to better serve Canadians.Footnotes18

The Universities Project was developed to provide students with a better understanding of the advantages of linguistic duality and to help maintain or improve their skills in their second language. The ultimate goal is to foster a pool of bilingual university graduates intending to pursue a career in the public service.Footnotes19 By facilitating this renewal of a bilingual public service, the Universities Project contributes to the Roadmap's stated objectives.

Part VII of the Official Languages Act (OLA) outlines the federal government's commitment toward the development of English and French linguistic minority communities as well as the recognition of linguistic duality in Canadian society. Section 41 of Part VII obligates federal institutions to take positive measures to implement this commitment.Footnotes20

The Universities Project aligns with the OLA through the provision of second language learning products to Canadian universities and thus contributed to:Footnotes21

- encouraging and supporting the learning of English and French in Canada;

- fostering an acceptance and appreciation of both English and French by members of the public; and

- encouraging and assisting organizations and institutions to project the bilingual character of Canada in their activities in Canada.

The Universities Project also shows alignment with the School's objectives, particularly in ensuring that potential public servants are able to perform their job and take on the challenges of the next job in a dynamic, bilingual environment.Footnotes22 This project contributes to this objective by facilitating official languages capacity through efficient access to a supply of language training services and facilitating language maintenance.

Opinions collected through the key informant interviews conducted for this evaluation also suggest widespread agreement that the Universities Project is in line with and contributes to achieving both federal government and the School's objectives by facilitating the renewal of a bilingual public service. To better prepare potential public servants for the federal context, the lessons included in the Universities Project learning modules include vocabulary consistent with the public service workplace and contain lessons promoting linguistic duality.

3.1.3 The Universities Project supports the role and mandate of the federal government

To this end, the Action Plan for Official Languages calls for the federal government to play a leadership role and lead by example in marrying together the two founding peoples, English and French, into a viable nation.Footnotes23 With the Universities Project, the federal government is ensuring the equal delivery of services to Canadians in both French and English.

However, during the key informant interviews, there was some disagreement regarding whether it is the School's mandate to provide services to individuals outside of the federal public sector. Some key informants felt that the Universities Project was investing in potential public servants, increasing the pool of new recruits that do not require expensive language training to refresh or improve their second language skills.

3.2 Effectiveness of the Universities Project

The Universities Project provides access to quality tools and accompanying support. Participants who have remained engaged with the project seem to have improved their second language skills. While this indicates that the project has met its performance objectives, the reach of these achievements has been limited by two main barriers: technical issues and the challenges associated with keeping participants engaged.

3.2.1 University satisfaction with tools and services provided through the Universities Project

Overall, key informants said that they were pleased with the quality of the tools provided by the Universities Project and recognized their potential to teach second language skills. Some key informants did highlight differences between the French and English core programs. The English program is a commercial product; therefore it was not tailored to a federal government context. Some also felt the content in the core English program was dated. It should be noted that the School is currently developing its own core English program.

One university coordinator also mentioned another distinct difference between the French and English programs. According to this coordinator, the English program was better for supporting the development of speaking skills and the French program was better for preparation for the standardized tests.

Ceux qui apprennent l'anglais sont en immersion (dans la communauté) donc ils ont plus de chance de pratiquer l'oral. Mais pour ce qui s'agit de la préparation au test, ceux qui apprennent le français ont l'avantage. – University coordinator

Furthermore, some coordinators did feel that the bulletins provided to the guided learners were inconsistent in terms of intensity or quantity of content. It was mentioned that some bulletins were quite intensive and required an unrealistic amount of time and work for students to complete.

Parfois, le contenu, je le trouvais lourd. Parfois il a avait beaucoup à assimiler en peu de temps. Les étudiants avaient déjà une charge lourde avec leurs cours. – University coordinator

Others also felt that even though the content of the bulletins focused on language used in the federal public service, activities and examples could have been more pertinent to students.

Technical issues with project delivery

In comparison to the minor remarks discussed above, a more significant area of dissatisfaction expressed by university coordinators was around the technical aspects of the project. The number and variety of technical difficulties encountered is said to have monopolized much of the university coordinators' time and resources and also discouraged many students from actively participating in the project.

Owing to the amount of funding available, the Universities Project could not develop its own operating platform. Consequently, the learning tools were originally provided through Campusdirect, the existing platform used by the School for all other online tools. Prior to the launch of the Universities Project, a transition to an Integrated Learning Management System (I-LMS) platform was already planned. When this transition occurred, more technical issues were reported.

La plateforme n'a pas été perfectionnée et, même aujourd'hui, elle n'est pas parfaite. Donc ceci a découragé beaucoup de participants. Les jeunes ne sont pas patients et s'ils ne sont pas satisfaits avec la plateforme, ils ne persistent pas. – University coordinator

Some of the technical issues reported included:

- security problems associated with providing access to an external client;

- issues with the capacities of the platforms selected to support the products; and

- compatibility with various hardware and software packages.

When it became clear that there were other outstanding issues associated with the new platform, the School began actively exploring other options to better deliver the Universities Project. The School began supporting the Universities Project through the use of an alternate platform in January 2012 which seems to be functioning well to date.

Given the technical issues experienced throughout much of the project, the School attempted to provide the best service and technical support possible. University coordinators were satisfied with the timeliness of the response from the School staff and the technical support provided for resolving their issues.

3.2.2 Participant satisfaction with tools and services provided through the Universities Project

Level of interest and motivation to participate in the Universities Project

According to university coordinators, students showed a lot of initial interest in the project. Some universities received more applications from students than could be accommodated. These universities used approaches such as a screening process or a lottery to select candidates. Some universities, however, did report high initial interest but received fewer applications to the project than expected.

University coordinators reported that the biggest motivator for student participation was the opportunity to create a government-recognized language profile. Many coordinators and participants expressed the perception that having the language profile was a "foot in the door" to employment with the federal public service.

A number of students credit already having done the test to giving them an advantage in getting their COOP placements. It made them more desirable to employers because this meant less administrative and HR work. – University coordinator

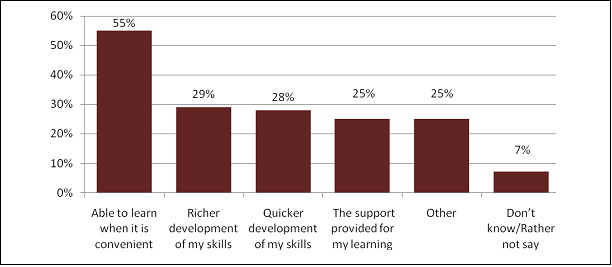

Chart 3-1 illustrates other common motivators to participate in the Universities Project as indicated by participants through the online survey. More than half of responding students (55%) indicated the ability to learn when it is convenient was a motivator to participate. The expectation that participation could lead to richer (29%) and quicker (28%) development of their second language skills were also commonly selected by survey respondents, as was the anticipated support for their learning (25%).

Chart 3-1: Aspects of the Project that Made Participants Decide to Participate

Text version

Chart 3-1 illustrates other common motivators to participate in the Universities Project as indicated by participants through the online survey. More than half of responding students (55%) indicated the ability to learn when it is convenient was a motivator to participate. The expectation that participation could lead to richer (29%) and quicker (28%) development of their second language skills were also commonly selected by survey respondents, as was the anticipated support for their learning (25%). 25% of the respondents mentioned other reasons that are not detailed in the chart, while another 7% selected don't know or rather not say.

Source: Online survey of participants

n = 75

Participants who completed the School administered surveys expressed agreement with various benefits of enhancing their second language skills, as summarized in Table 3-2.

Table 3-2: Agreement Levels Regarding Motivations to Participate in the Universities Project

Table 3-2 shows agreement levels regarding motivations to participate in the Universities Project. The first column identifies the statements on the basis of which the participants expressed their opinion. The second column indicates which percentage of the participants strongly agreed or agreed with the statements.

| |

Strongly agree /

Agree |

| I wish to learn my second official language to take advantage of employment or professional development opportunities |

98% |

| I would like to have a good command of my second official language |

96% |

| I would like to become comfortable enough in my second official language to interact with native speakers |

96% |

| I am motivated to learn my second official language |

92% |

| Learning my second official language will have an impact on my life |

92% |

| I am willing to work hard at learning my second official language |

91% |

| I enjoy learning my second official language |

87% |

| External factors such as the job market influence my motivation to learn my second official language |

80% |

| I wish to learn my second official language to become culturally enriched |

78% |

| My goal is to become self-reliant in my second official language to travel abroad |

67% |

Source: The School's administered participant motivation survey

n = 134

Level of student engagement

Despite initial interest and motivations, there was an overall lack of participant engagement throughout the Universities Project, including a salient proportion of withdrawals. Overall, 46% of project participants formally withdrewFootnotes24 from the project (Table 3-3 provides the project enrolment compared to the total formal withdrawals from the project).

It should be noted that a certain level of withdrawal was expected from the outset. Approximately 250 participants were expected to be recruited across all universities with a requirement to maintain a minimum of 100 (10 per universityFootnotes25 ,Footnotes26 for the duration of the project. Considering the enrolment data, a total of 153 participants remain enrolled, more than the minimum required; however, the actual level of participation is likely to be lower as students may have stopped participating in the project, despite not formally withdrawing.

Table 3-3: Formally Withdrawn Participants Compared to Initial Enrolment

Table 3-3 represents formally withdrawn participants compared to the initial enrolment. The first column enumerates the name of the participating universities. The second column indicates the total enrolment per university. The third and the fourth columns show the number of withdrawals and the percentage of withdrawals respectively.

| |

Total Enrolment |

Withdrawn |

Percentage Withdrawn |

| York University – Glendon Campus |

29 |

22Footnotes* |

76% |

| Simon Fraser University |

32 |

22 |

69% |

| University of Ottawa |

37 |

23 |

62% |

| University of Waterloo |

29 |

18 |

62% |

| University of Regina |

36 |

21 |

58% |

| University of Alberta |

14 |

5 |

36% |

| Université Sainte-Anne |

18 |

5 |

28% |

| École national d'administration publique |

29 |

5 |

17% |

| University of Victoria |

31 |

5 |

16% |

| Carleton University |

27 |

3 |

11% |

| Total |

282 |

129 |

46% |

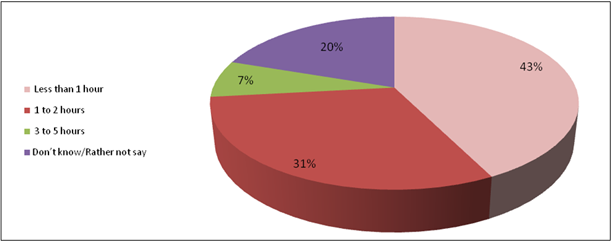

Results from the online survey of participants also provide further indication of the limited level of participation in the project. Only 4% of respondents indicated currently participating in the project and being up to date with the learning activities, 44% said they were participating, but were behind in the learning activities and 48% indicated they were not currently participating in the project. Of the participants who indicated that they were no longer participating in the project, more than half had not formally withdrawn. Thus, even among participants who had not formally withdrawn, many were not actively engaged in the project.

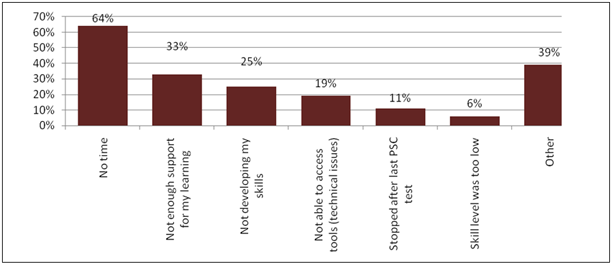

Survey respondents who indicated they were not currently participating in the project were asked to specify reasons. As demonstrated in chart 3-2, the most common reason for not participating was lack of time (64%). The next most commonly selected reasons for not currently participating speak to their experiences with the project, including a lack of support for their learning (33%) and their participation was not developing their skills (25%).

Chart 3-2: Reasons for Not Currently Participating in the Project

Text version

Chart 3-2 depicts reasons for not currently participating in the project. Survey respondents who indicated they were not currently participating in the project were asked to specify reasons. As shown in the chart, the most common reason for not participating was lack of time (64%). The next selected reasons for not currently participating speak to their experiences with the project, including a lack of support for their learning (33%), that their participation was not developing their skills (25%), that they were not able to access tools (19%), that they stopped after last PSC test (11%), and that their skills were too low (6%). 39% said it was for other reasons which are not identified in the chart.

Source: Online survey of participants

n = 36 – represents the 48% of online survey respondents who indicated they were no longer participating in the project

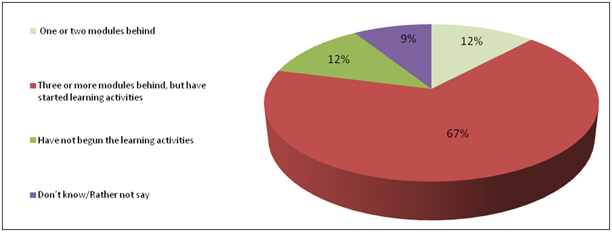

To develop a better understanding of participants' level of engagement, survey respondents who indicated they were currently participating but were behind in the learning activities (44%) were asked how far behind they were. Responses are illustrated in Chart 3-3.

Chart 3-3: Extent to which Participants are Behind in the Learning Activities

Text version

Chart 3-3 visually demonstrates the extent to which participants were behind in the learning activities. The pie chart shows that 67% of the participants were three or more modules behind, but have started learning activities. 12% of the participants stated that they were one or two modules behind; while another 12% admitted they have not begun the learning activities. 9% of respondents selected don't know or rather not say.

Source: Online survey of participants

n = 33

The majority of these respondents (67% or 29% of all respondents) were at least three modules behind, but had started the learning activities. This chart also shows that 12% of those who were behind but had not withdrawn from the project (5% of all respondents) never began any learning modules.

Satisfaction with tools and services

While data collected for this evaluation suggest a high proportion of disengagement from the project, there was a group of engaged participants who did express considerable agreement with statements about the tools and services provided (Table 3-4). Agreement was particularly high with the visual aids and activities, content and usability of the tools. It is also interesting to note that agreement levels were almost always lower among survey respondents who were guided learners. There was less agreement that effective technical support was available, that there were clear instructions for using the tools, or that objectives of the learning phases had been met. It should be noted that the final survey completions were largely comprised of those who had continued with the project. The satisfaction with the tools and services among those who withdrew from the project remains largely unknown.

Table 3-4: Participant Satisfaction with Tools and Services

Table 3-4 shows participant satisfaction with tools and services. The first and fourth columns contain statements on the basis of which participants had to express their opinion. The second and fifth columns indicate which proportion of self-directed participants strongly agreed or agreed with the statements, while the third and sixth columns indicate which proportion of guided participants strongly agreed or agreed with the same statements. Some cells are blank because the questions were not applicable or included.

|

Strongly agree / Agree |

|

Strongly agree / Agree |

| |

Self -Directed |

Guided |

|

Self-Directed |

Guided |

| The on-screen graphics and text were easy to read |

82% |

70% |

The products and tools maintained my interest |

51% |

41% |

| The audio and video activities were effective in helping me learn |

77% |

62% |

The approach was a suitable language training method |

51% |

49% |

| The content in this learning initiative was appropriate |

69% |

|

The technical support from my university was effective in providing access to the products and tools |

51% |

57% |

| The learning materials were easy to use |

69% |

60% |

The instructions for using the products and tools were clear |

49% |

46% |

| The learning phase/activities in the products were well structured |

64% |

49% |

The technical support from the School was effective in providing access to the products and tools |

41% |

51% |

| The products and tools were easy to navigate |

64% |

62% |

The learning objectives were met |

33% |

35% |

| The products and tools were interactive |

64% |

65% |

The learning objectives were understood |

|

68% |

| Overall, I was satisfied with this learning phase/initiative |

62% |

49% |

The learning objectives were relevant |

|

62% |

| The description of the products and tools was accurate |

62% |

54% |

I was satisfied with the materials used in the learning phase |

|

46% |

| The exercises were effective in helping me learn |

62% |

49% |

The bulletin (newsletter) content was easy to read and navigate |

|

57% |

| E-learning was an appropriate delivery method for this content |

62% |

43% |

The learning activities in the products were well structured |

|

46% |

| The instructional methods were effective in helping me learn |

54% |

43% |

The learning support from my university for this learning phase was effective in helping me learn |

|

51% |

Source: The School administered participant satisfaction survey

n = SDL: 39, GL: 37

Responses that were not applicable were not included.

Online survey respondents were also asked about their satisfaction with the support provided by their university and if the project lived up to their expectations (Table 3-5).

Table 3-5: Survey Participants who Agree with Statements about Satisfaction with Universities ProjectsFootnotes*

Table 3-5 represents survey participants who agree with statements about satisfaction with Universities Project. The first column lists the statements. The second column indicates the percentage of participants that responded to the questions. The third and fourth columns state the percentage of responses for self-directed and guided respondents respectively. The fifth and sixth columns show the proportion.

| |

Total

n = 75 |

Self-Directed

n = 31 |

Guide

n = 44 |

Learning

EN

n = 22 |

Learning

FR

n = 53 |

| I was able to access someone at the university to provide me support in the project when I required it. |

52% |

52% |

52% |

45% |

55% |

| I am satisfied with my university's level of engagement with the project. |

37% |

45% |

32% |

50% |

32% |

| The project lived up to my expectations. |

19% |

23% |

16% |

32% |

13% |

Most participants agreed that they did have access to someone at their university when required; however, fewer agreed that they were satisfied with their university's level of engagement with the project. Only one in five survey respondents perceived that the project had lived up to their expectations. It should be noted that more English learners agreed with statements about expectations and their university's engagement. As only three schools offered the English learning path to their students, this higher level of agreement may be a result of the particular efforts of those universities.

Comparing the Universities Project to other learning programs

Respondents to the online survey were also asked a series of questions to explore the availability of other language learning tools and how these compared to the Universities Project.

Opinions were mixed when comparing the Universities Project's tools and content to other online learning programs. Online survey respondents were first asked if they had used other online learning tools and of the 51% who indicated they had, the group was equally split between those who felt the Universities Project was the same (32%), worse (29%) or better (24%) than these tools.

Respondents were also asked if they had access to other programs that would develop their second language skills. Most said they did not have access to such programs (57%). Of those that had participated in these other programs, a higher proportion said the Universities Project was worse (58%) and one quarter said it was about the same (25%). When asked for a reason for this comparison, respondents felt that the Universities Project lacked the crucial elements of in-person interaction and speaking practice.

Online exercises are good for things like memorizing grammar rules and learning new vocabulary, but it is no substitute for conversation. – Project participant

3.2.3 Impact of the Universities Project on participants

Perhaps the most important means of evaluating the Universities Project is to understand whether it had an impact on participants' appreciation for linguistic duality and/or the degree to which it improved their proficiency in their second official language.

Increased understanding of linguistic duality

Results from the online survey do indicate that respondents agree that it is important to learn their second official language (91%, See table 3-6). However, a lower proportion agreed that they had a better understanding of the advantages of communicating in two languages since participating in the project. This lower agreement rate may signify that participants already had a sound understanding of the advantages of linguistic duality before participating in the project. Conversely, it may be due to a lack of communication about this element of the project as one university coordinator indicated that this element was not visible enough.

It was efficient and effective for learning language; however the element of linguistic duality could have been made more prominent. Most of the students did not know that was part of the project. – University coordinator

Table 3-6: Survey Respondents Who Agree with Statements about Linguistic DualityFootnotes*

Table 3-6 indicates the proportion of survey respondents who agree with statements about linguistic duality. The first column lists the statements. The second column indicates the total percentage of participants that evaluated the statements. The third and fourth columns state the percentage of responses of self-directed and guided respondents respectively. The fifth and sixth columns show the proportion of respondents who studied in English and French respectively.

| |

Total

n = 75 |

Self-Directed

n = 31 |

Guide

n = 44 |

Learning

EN

n = 22 |

Learning

FR

n = 53 |

| It is important for me to learn <French/English>. |

91% |

94% |

89% |

91% |

91% |

| I have a better understanding of the advantages of communicating in two languages since I began participating in the project. |

44% |

55% |

40% |

55% |

36% |

Increased proficiency in participants' second language

All participants were given the opportunity to complete the Public Service Commission's second language test administered by the Public Service Commission at the beginning of the project. This test is a government-recognized measure of participants' communication abilities in their second official language and formed a baseline to measure the performance of the project. The participants were then given the opportunity to complete the test again at the end of the project to measure the degree and nature of the change in their second-language communication skills. The analysis here looks for participants who improved their test scores over the course of the project. Consequently, only those participants with both a pre- and a post-test score can be analyzed.

Table 3-7: Percentage of Participants Achieving a Level Change on Second Language Tests

Table 3-7 indicates the percentage of participants that have achieved a level change on second language tests. The first column lists the types of change in second language tests. The second column indicates the percentage of participants that had a change in their reading skills. The third column indicates the percentage of participants that had a change in their writing skills. The last column indicates the percentage of participants that had a change in their oral skills.

| Change |

Reading

(n = 25) |

Writing

(n = 20) |

Oral

(n = 27) |

| A to B |

22% |

38% |

40% |

| B to C |

44% |

70% |

20% |

| C to E |

43% |

0% |

0% |

Source: Administrative data

Note: Only the results for students who completed both pre- and post-tests are displayed.

The results detailed in Table 3-7 do seem to indicate that the tools helped develop second language skills across the learning levels, from beginners to more advanced learners. For instance, 70% of those who had scored a B in writing in the pre-test scored a C in the post-test. Although the results here should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample sizes (for instance, only two respondents scored a C for writing in the initial test), the results may suggest that the project was particularly helpful in developing advanced learners' reading skills, intermediate learners' writing skills, and beginner learners' oral skills. At least for participants who did not withdraw and remained engaged in the project, the tools and services improved a range of participants' second language proficiencies.

Looking at the test results by learning approach and by language, significant differences in the level of improvements can be found (Table 3-8). This data suggests that participants learning English were considerably more successful in achieving a change in proficiency level. Fewer participants learning French measurably improved their skills. Evidence providing reasons for this considerable difference was not found through this evaluation. Therefore any such discussion would be speculative. However, this finding is of interest and could be explored further by the School.

Table 3-8: Percentage of Participants Achieving a Level Change on Second Language Tests by Learning Approach and LanguageFootnotes27

Table 3-8 indicates the percentage of participants that achieved a level change on second language test by learning approach and language. The first column lists the learning approaches. The second column indicates the percentage of participants that have achieved a level change in their reading skills, while the third and fourth columns present the percentage of participants that have achieved a level change in their writing and oral skills respectively.

|

Reading

(n = 25) |

Writing

(n = 20) |

Oral

(n = 27) |

| EN Guided |

75% |

40% |

43% |

| EN Self-Directed |

44% |

50% |

43% |

| FR Guided |

14% |

50% |

13% |

| FR Self-Directed |

20% |

60% |

20% |

| Total |

36% |

50% |

30% |

Source: Administrative data

Note: Only the results for students who completed both pre- and post-tests are displayed.

It should also be noted that these results represent only those participants who achieved a full level change during the project (i.e. from A to B or B to C)Footnotes28 , a fairly significant improvement. It is likely that many other participants did achieve improvement within their level. It also should be noted that no participant regressed significantly in any of their language proficiencies during the project period (i.e. from B to A).

Furthermore, the impact of the Universities Project may be underestimated in this analysis, as some participants were asked to complete their second Public Service Commission's second language test before completing the curriculum entirely. Thus not all participants' second language skills development was measured.

To gain a sense of all levels of language skill improvements, respondents of the online survey were asked how they felt about their skills after participating in the project. While 32% of respondents agreed they were more able and 29% agreed they were more confident to communicate in their second language since their participation in the project, a larger proportion disagreed with these statements (Table 3-9).

Table 3-9: Survey Level of Agreement with Statements about Increasing Proficiency

Table 3-9 presents the survey level of agreement with statements about increasing proficiency. The first column enumerates the statements. The second column shows the percentage of participants that strongly agreed or somewhat agreed with the statements. The third column shows the percentage of participants that neither agreed nor disagreed with the statements. The fourth column shows the percentage of participants that strongly disagreed or somewhat disagreed with the statements.

|

Strongly Agree / Somewhat Agree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Strongly Disagree / Somewhat Disagree |

| I am more able to communicate (speak, read and write) in <French/English> since I began participating in the project. |

32% |

19% |

37% |

| I am more confident to communicate (speak, read and write) in <French/English> since I began participating in the project. |

29% |

19% |

40% |

Source: Online survey of participants

n = 75

Thus for some participants the Universities Project appears to have helped improve their second language proficiencies and this was measurable by the standardized tests. For others the project appears to have done little to enhance their abilities in their second language. Considering the lack of engagement with the project, this may have been a primary barrier to their learning.

3.2.4 Extent to which the Universities Project facilitates access to the School's language learning tools

While there is no data available demonstrating usage, or access to these tools by participants throughout the project, data was available for the period between January and August 2010.Footnotes29 To provide an idea of the level of usage throughout this period, an analysis of access to the two core programs was completed (Table 3-10).

This analysis demonstrates that access to the online tools varied considerably by school. Based on the results, all participants from the University of Alberta accessed the online tools at least once in the eight months from January to August, 2010. Participants at the École nationale d'administration publique (ENAP), and the University of Regina and Simon Fraser University also had high instances of access.

For other schools, only a modest proportion of participants accessed the tools. In fact, less than half of the participants from the University of Ottawa, University of Victoria and Glendon Campus accessed the tools at all during this eight-month period. This analysis is based on all participants, and not actively participating participants. In other words, the findings for the Ottawa, Glendon and Victoria universities above could be a measure of withdrawal from the project at these schools as much as access to the online tools. However, when an analysis is done of the average number of accesses per login account, a similar story unfolds. Participants at ENAP who did access the tools did so nearly 32 times on average. Participants at the University of Regina and Simon Fraser University also accessed the online tools frequently. For these schools, not only were their participants likely to use the online tools, but they were more likely to use them frequently.

Table 3-10: Core Program Usage (January to August, 2010)

Table 3-10 demonstrates the core program usage between January and August 2010. The first column indicates the evaluated tools, while the second column lists the participating universities. The third column displays the number of participants for each university. The fourth column presents the number of participants who have accessed the program. The fifth and sixth columns present the access frequency and the percentage of participants who accessed the program respectively. The seventh column indicates the access frequency of the participants.

| Tool |

University |

Participants |

Participants Accessing |

Frequency of Access |

% of Participants Accessing |

Frequency of Access for those Accessing |

| French Self-directed |

University of Alberta |

14 |

14 |

163 |

100% |

11.6 |

| Carleton University |

27 |

14 |

121 |

52% |

8.6 |

| York University – Glendon Campus |

29 |

11 |

126 |

38% |

11.5 |

| University of Regina |

36 |

28 |

511 |

78% |

18.3 |

| Université Sainte-Anne |

13 |

10 |

207 |

77% |

20.7 |

| Simon Fraser University |

32 |

24 |

382 |

75% |

15.9 |

| University of Ottawa |

21 |

8 |

46 |

38% |

5.8 |

| University of Victoria |

31 |

12 |

40 |

39% |

3.3 |

| EnglishFootnotes30 |

École national d'administration publique |

29 |

25 |

798 |

86% |

31.9 |

| Université Sainte-Anne |

5 |

2 |

9 |

40% |

4.5 |

| University of Ottawa |

15 |

6 |

41 |

40% |

6.8 |

Source: Administrative Data

Note: Participants accessing is defined by the number of unique users accessing the system.

Participants at other schools accessed the tools much less frequently, even among those who did access the tools at least once from January to August, 2010. A particular case in point may be the University of Victoria. Not only did more than 60% of their participants not access the online tools at any time during these eight months, but those that did only did on average about three times.