CSPS Strategic Directions Initiative Integrated Summative Evaluation

May 2018

Integrated Summative Evaluation - Final

List of acronyms

CCSD

Core Committee on Strategic Directions

CSPS

Canada School of Public Service

FAA

Financial Administration Act

FTE

Full-Time Equivalent (person-year)

I-LMS

Integrated Learning Management System

ILT

Instructor-Led Training

IM

Information Management

IT

Information Technology

OCHRO

Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer

SDI

Strategic Directions Initiative

SPOC

Strategy, Planning and Operations Committee

SSC

Shared Services Canada

TB

Treasury Board of Canada

Executive summary

Background and context

In November 2014, the Treasury Board (TB) approved the Strategic Directions Initiative (SDI, or the Initiative) as a phased project over 3 years (2014–15 through 2016–17) to examine the delivery and management of learning at the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS, or the School), as well as programming, the underlying business model, and the supporting strategies needed to implement a new model. The Initiative aimed to put in place a more accessible, relevant and responsive learning platform. The Initiative included plans to modernize the School's business operations and change the funding model to establish a new approach to learning. In this new approach, departments would focus on mandate-specific learning while the School would deliver a relevant, common curriculum for the public service, and advances a public service-wide culture of learning.

The past 3 years saw considerable activity in terms of consultations with federal government departments and agencies, the phasing in of the new funding model, the revision of the curriculum, and the development of supportive learning technologies and business intelligence systems. As of the end of 2016–17, public servants can now access the School's online platform, GCcampus, with its suite of learning products, from anywhere internet access is provided.

Evaluation purpose and scope

An evaluation of the Initiative was undertaken to provide neutral, credible, and timely feedback to School decision-makers based on the commitments made to the Prime Minister and the Treasury Board in 2014. Two evaluation exercises were conducted. A formative evaluation providing a mid-term assessment of the Initiative was delivered in December 2016. The formative evaluation focused on implementation and addressed questions primarily related to SDI activities, outputs and immediate outcomes. The CSPS Strategic Directions Initiative: Integrated Summative Evaluation focuses on questions related primarily to intermediate and long-term outcomes; specifically, the summative evaluation examined, post-SDI, the adequacy of School funding and the appropriateness of School authorities, the extent to which learner satisfaction, knowledge and application of knowledge increased, the relevance of the School's curriculum, the impact of SDI on the range of CSPS learning products, the extent to which a common, core curriculum was established, and the School's performance in terms of reporting on training outcomes. The summative evaluation also examined the question of how the School can measure, in the future, the outcomes of its learning ecosystem.

Conclusions and recommendations

The new CSPS funding model has been successfully adopted, and planned reference levels and spending authorities appear to be appropriate. Because activities undertaken as part of SDI are still stabilizing and will continue to do so for at least 2 more years, and future demand is difficult to predict so early in the life span of the new model, it is premature to assess with certainty the future resource requirements of the School. That said, it would appear that current reference levels for 2017–18 and beyond will be sufficient in the near term, with the caveat that further augmentations in School responsibilities might need to be accompanied by additional funding.

Retaining the authority to collect fees, and to carry over revenues from these fees to the next fiscal year, provides an appropriate level of flexibility for the School to efficiently and effectively implement the new business model.

Recommendation 1. It is recommended that, in future, estimated costs associated with the development and delivery of learning become a distinct element of consideration in Treasury Board submissions and Cabinet requests.

The School has established a relevant core common curriculum, as defined by senior officials. The School made substantial progress toward the establishment of a relevant core common curriculum. The School's focus is seen to have been sharpened, and department and agency representatives have greater confidence that the School can meet basic learning needs, leaving to departments and agencies mandate-specific training.

The core common curriculum is defined, in essence, as the topics and priorities deemed to be relevant to the performance responsibilities of a critical mass of public servants enterprise-wide, along with priorities identified at senior levels. The definition has not been systematically validated at the front-line level, however. Also, the idea of learner needs having to be "enterprise-wide" appears to have precluded training for significant subpopulations; officials in some departments and agencies believe their employees' needs fall largely outside the purview of the School's new definition, and are left having to provide required training themselves.

Recommendation 2. It is recommended that the School, in consultation with senior officials as well as middle managers and front-line staff across all regions, continues to clarify, validate and refine the definition of its core common curriculum.

The School's range of learning products was extensively overhauled, improving accessibility and choice among learning modes. Under SDI, the range of CSPS learning products changed substantially. The number of classroom courses fell from 262 to 87 while the number of events increased nearly fivefold to 372. The number of self-paced online learning products remained relatively stable (at 219 as of the end of 2016–17), but almost all were replaced with newer versions. In addition, new types of learning products were made available.

Department and agency representatives are generally positive respecting the renewed range of learning products, noting significant improvements in terms of learning mode choice and in the accessibility of learning opportunities. The School appears better able to respond rapidly to emergent priorities. Concerns remain, however, related to the shift from a model emphasizing classroom-based training to one relying more on online learning activities. Fewer classroom options can lead to perceptions among users about possible seat shortages. Also, an overreliance on online modes can impede training for employees without ready access to the internet.

Recommendation 3. It is recommended that the School continues to develop and optimize the range of learning modes associated with its learning ecosystem.

The School has yet to establish a robust outcomes measurement regime. CSPS has collected Level 1 evaluation data since long before SDI, and found through its Level 1 data tracking efforts that satisfaction with self-paced online learning products increased over the SDI period. Level 1 observations are, however, of the least interest to department and agency representatives who are keener to know the extent to which their employees are acquiring new knowledge and skills from their School experiences and the extent to which they are applying these learnings on the job.

The School collects elementary knowledge acquisition and learning application data on most activities for which registration is required, plus detailed data on a small sample of learning activities each year, but it has not developed an analysis protocol sufficient to satisfy client organizations. Moreover, in light of the evolution of the School's learning ecosystem, a system that appropriately and effectively measures learning outcomes will need to go beyond traditional evaluation concepts (the Kirkpatrick model) and traditional evaluation data collection approaches. Departments and agencies must be involved in data collection. In short, a more comprehensive and strategic approach is required to meet the demands of departments and agencies, as well as the needs of the School, by which methodologies are adopted in line with evaluation needs.

Recommendation 4. It is recommended that the School builds upon existing learning evaluation practices, and invests appropriately to create a comprehensive evaluation regime capable of collecting, analyzing, and reporting on data in relation to satisfaction, learning, application and other concepts according to the needs of users.

SDI has given the School an upgraded business intelligence system capable of generating a wide range of reports; internal reports have been well received, however, client organizations remain unsatisfied. As a result of the activities undertaken as part of the Initiative, the School has invested in an upgraded business intelligence system that, combined with existing data collection practices, is capable of providing a wide range of outcome metrics. School officials are generally satisfied with reports generated for internal use. Various iterations of external report models, however, have yet to fully satisfy the needs of client departments and agencies. Department and agency officials want monthly usage figures, information on completions and cancellations, and learning outcome metrics for their employees including statistical information such as response rates.

Recommendation 5. It is recommended that the School improve its external reporting by establishing a system that generates reports that meet client requirements in terms of frequency, content, and format.

1. Introduction

An evaluation of the CSPS Strategic Directions Initiative was undertaken to provide neutral, credible, and timely feedback to Canada School of Public Service (CSPS, or the School) decision-makers based on the commitments made to the Prime Minister and the Treasury Board in 2014. It aims to inform the extent of achievement against expected outcomes set out for the Strategic Directions Initiative (SDI, or the Initiative). The School is committed to reporting these results to the Privy Council Office and the Treasury Board by the end of the 3rd quarter, 2017–18.

Two evaluation exercises were conducted. A formative evaluation providing a mid-term assessment of the Initiative was delivered in December 2016. The formative evaluation focused on implementation and addressed primarily questions related to SDI activities, outputs and immediate outcomes.

The present report, CSPS Strategic Directions Initiative: Integrated Summative Evaluation, focuses on questions related primarily to intermediate and long-term outcomes, presenting the results of evaluation activities undertaken between June and September 2017. The report begins with a description of the Initiative, followed by the evaluation objectives and methodology, and the findings of the evaluation organized by evaluation question. The report ends with conclusions, recommendations, and a management response and action plan.

2. Background and context

2.1 Impetus for the Strategic Directions Initiative

The School operates under the Canada School of Public Service Act, which states as objectives for the School "to encourage pride and excellence in the public service… to help ensure that managers have the … skills and knowledge necessary to develop and implement policy, respond to change… and manage government programs, services and personnel efficiently, effectively and equitably… [and] to help [all] public service employees… [to deliver] high-quality service to the public."

On November 24, 2014, the Treasury Board (TB) approved the Strategic Directions Initiative as a phased project to be rolled out over 3 years (2014–15 through 2016–17) to examine the delivery and management of learning, the School's programming and underlying business model, and the supporting strategies needed to implement it. Prior to the launch of the Initiative, learning delivery was considered piecemeal and not always directly linked to government priorities or performance needs. The cost-recovery funding model in place at the time encouraged a focus on revenue-generation, and access to learning was unequally distributed across regions and organizations.

The Initiative defined an end-to-end transformation of learning, both in terms of what was being taught as well as how it is taught. The project aimed to put in place a more cost-effective and accessible learning platform. The Initiative included plans to modernize the School's business operations and change the funding model to establish a new approach to learning, delivered in partnership with specialists from the public sector, the private sector, and academia. In this new approach, departments would focus on mandate-specific learning opportunities while the School would deliver a relevant, common curriculum for the public service,Note 1 and advance a public service-wide culture of learning.

2.2 Expected outcomes

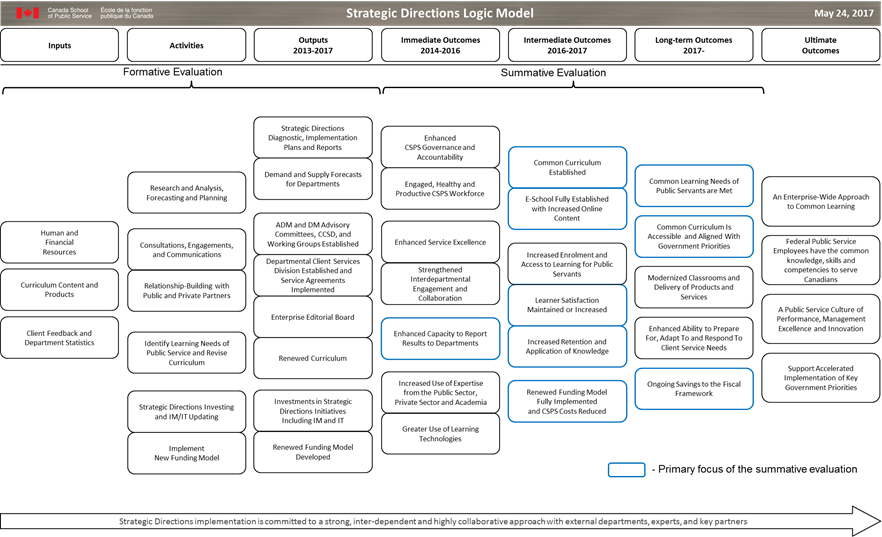

Based on TB approval in November 2014, the following logic model was developed to guide the Initiative's implementation. Boxes outlined in blue comprise the outcomes on which the integrated summative evaluation focused. The achievement of other outcomes was examined through the mid-point assessment conducted in 2015 and 2016. Expected outcomes as they relate to the 2 evaluation exercises are described in more detail in Chapter 3.

Text version of the Strategic Direction Logic Model graphic

This graphic shows the Strategic Directions Logic Model, which operates as a road map. An arrow indicates the direction of the road map as moving left to right from Inputs to Ultimate Outcomes. The arrow is labelled, "Strategic Directions implementation is committed to a strong, inter-dependent and highly collaborative approach with external departments, experts, and key partners."

The first 3 components on the road map (Inputs, Activities, and Outputs 2013–2017) feed into the Formative Evaluation. The next 3 components (Immediate Outcomes 2014–2016, Intermediate Outcomes 2016–2017, and Long-term Outcomes 2017– ) feed into the Summative Evaluation. The final component on the roadmap is Ultimate Outcomes.

Of the 18 elements listed as making up the Summative Evaluation components, 9 are identified as the primary focus of the Summative Evaluation. These are: Enhanced Capacity to Report Results to Departments, Common Curriculum Established, E-School Fully Established with Increased Online Content, Learner Satisfaction Maintained or Increased, Increased Retention and Application of Knowledge, Renewed Funding Model Fully Implemented and CSPS Costs Reduced, Common Learning Needs of Public Servants are Met, Common Curriculum is Accessible and Aligned with Government Priorities, and Ongoing Savings to the Fiscal Framework.

2.3 Current status of the Initiative

The past 3 years have seen considerable activity in terms of consultations with federal government departments and agencies, the phasing in of the new funding model, the revision of the curriculum, and the development of supportive learning technologies and business intelligence systems. As of the end of 2016–17, public servants can now access the School's online platform, GCcampus, with its suite of learning products, from anywhere internet access is provided. As a result, the School's products are reaching an increasing number of public servants from across Canada. In 2013–14, the year preceding the Initiative, the total number of unique learnersNote 2 who used the School's common learning platform (classroom and online) was 100,962.Note 3 In the 3rd and final year of the Initiative, 2016–17, the number was 159,287, representing a 63% increase.

While most planned activities associated with the Initiative concluded by the end of fiscal year 2016–17, the Initiative budget was not entirely expended. Remaining budget has been carried forward to fund the institutionalization and refinement of Initiative components, extending through 2018–19.

2.4 CSPS expenditures and SDI investments

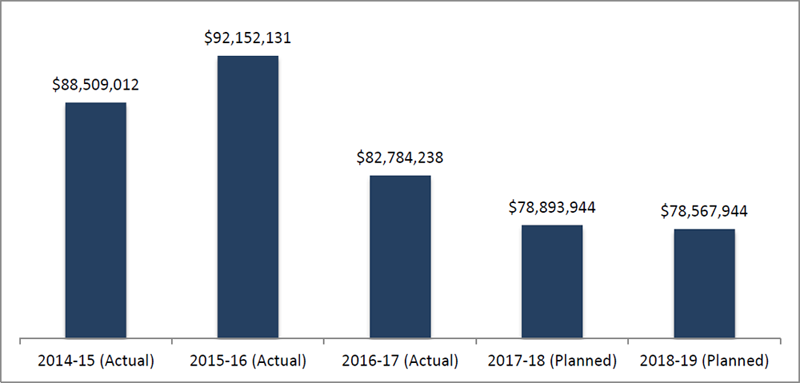

Figure 1 shows the actual and planned total expenditures of the School between 2014–15 and 2018–19. This expenditure period includes the 3-year transformation period, 2014–15 through 2016–17, as well as the 2 subsequent years.

Figure 1. CSPS expenditures by year from 2014 to 2019 (actual/planned)

Source: CSPS Departmental Results Report, 2016-17, and CSPS Report on Plans and Priorities, 2016-17

Source: CSPS Departmental Results Report, 2016-17, and CSPS Report on Plans and Priorities, 2016-17

Text version of the CSPS expenditures by year from 2014 to 2019 (actual/planned) graphic

Canada School of Public Service Expenditures presented by year in dollars. The expenditures, broken down by actual and planned amounts, are presented in a bar graph for fiscal years 2014–2015, 2015–2016, 2016–2017, 2017–2018, and 2018–2019. The amounts are as follows:

2014–2015

2015–2016

2016–2017

2017–2018

2018–2019

Table 1 shows the actual and planned investments to implement the Initiative between 2014–15 and 2018–19. It includes actual expenditures of $20.8 million over the 3-year transition period, and planned investments of $6.1 million over the 2 subsequent years, totalling $26.8 million over the 5-year period.

Table 1. Strategic Direction investment expenditures by year from 2014 to 2019 (actual and planned). Read down the first column for the investment projects, then to the right for the actual expenditures for 2014–2015, 2015–2016, and 2016–2017, followed by the planned expenditures for 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 and finally the total expenditures by category.

| |

2014–15 Actual |

2015–16 Actual |

2016–17 Actual |

2017–18 Planned |

2018–19 Planned |

Total by category |

| Modernization of Learning – Curriculum |

$865,113 |

$3,228,379 |

$3,823,660 |

$1,115,000 |

$1,040,000 |

$10,072,152 |

| Modernization of Learning – IT Updating |

$2,009,783 |

$2,850,536 |

$2,478,037 |

$1,840,000 |

$1,640,000 |

$10,818,356 |

| Business Intelligence |

$139,328 |

$952,451 |

$1,392,895 |

$13,000 |

$13,000 |

$2,510,674 |

| Facility Improvements |

$983,008 |

$836,527 |

$1,196,064 |

$200,000 |

$200,000 |

$3,415,599 |

| Total Expenditures (Annual) |

$3,997,232 |

$7,867,893 |

$8,890,656 |

$3,168,000 |

$2,893,000 |

$26,816,781 |

| Total Expenditures (Cumulative) |

$3,997,232 |

$11,865,125 |

$20,755,781 |

$23,923,781 |

$26,816,781 |

|

Source: CSPS files

Full-time equivalents (FTEs) decreased during the time span of the Initiative. In 2013–14 total CSPS FTEs were reported to be 622. In 2016–17, total FTEs were reported to be 581. Between 2014–15 and 2016–17 the School's physical footprint decreased from 36,866 square metres to 32,578 square metres.

3. Evaluation objectives and methodology

3.1 Mid-point assessment

The formative evaluation examined the Initiative's activities and outputs from 2013–14 through 2015–16, to assess whether the Initiative was being implemented as intended, and to determine the extent to which progress and achievements were made on selected expected outcomes. The formative evaluation involved a review of an extensive selection of School and related documentation and interviews with 56 representatives of the School, client organizations and other stakeholders. The formative evaluation provided an important tool for the CSPS management team to assess progress on the Initiative and to undertake course corrections as necessary. As a formative evaluation, the mid-point assessment also provided an important tool for assessing progress against criteria set out in the TB Submission.

The Mid-Point Assessment Report, approved in December 2016, confirmed that the School had undertaken an appropriate mix of activities and outputs to support the transformation to the new business and delivery model. The report also confirmed that School activities were sufficiently supported by the School's new governance and accountability structure and revealed strengthened interdepartmental engagement and collaboration with a variety of groups.

Key findings highlighted in the report include progress on the full implementation and roll-out of a common curriculum for federal public servants appearing on track for the end of 2016–17, involving a greater number of learning priorities than originally planned. This included learning on priorities such as results and delivery, Indigenous awareness, new directions in staffing and the policy suite reset, in addition to the objectives foreseen at the beginning of the transformation. Also, the report noted that the transformation to a new funding and delivery model has enhanced the reputation of the School as a focal point for common learning in the federal public service.

The mid-point assessment identified 5 recommendations. The School developed corresponding management responses and action plans. These are shown in Appendix A. Details on some of these actions (those connected to summative evaluation questions) are addressed in more detail in Chapter 4 of the Integrated Summative Evaluation.

The summative evaluation, covering the original implementation period (2013–14 to 2016–17),Note 4 addressed questions related to expected outcomes and other aspects of the Initiative not addressed under the formative evaluation. The summative evaluation was comprised of a statutory mandate review, outcomes review and a funding model review. Goss Gilroy Inc. was responsible for the statutory mandate review and outcomes review, as well as the final integrated summative evaluation report. The funding model review was conducted by a separate contractor. The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the new Treasury Board Policy on Results and Directive on Results, including the Directive's Appendix B: Mandatory Procedures for Evaluation.

3.2 Summative evaluation questions

Summative evaluation questions are shown in Table 2. The list specifies the evaluation questions (EQs) pertaining to the 3 reviews associated with the integrated summative evaluation, along with corresponding sources of evidence (see below). Questions addressed by the midpoint assessment are also included in the table, for reference.

Table 2. Summative evaluation questions and sources of evidence. Read down the first column for the evaluation components, then to the right for the evaluation questions, followed by the data sources, which are broken down as document review, interviews, administrative data, literature review, and funding model review.

| Evaluation component |

Evaluation question |

Data sources |

| Document review |

Interviews |

Admin. data |

Literature review |

Funding model review |

| Statutory mandate review |

1. Should the School's statutory mandate and revenue and spending authorities be adjusted to reflect its new mandate and business model? |

checkmark |

|

|

|

|

| Funding model review |

2. Was the amount reallocated to the School aligned with the level of ongoing expenditures required to deliver the new business model? |

|

|

|

|

checkmark |

| 3. Are the School's revenue and spending authorities appropriate? |

checkmark |

|

|

|

checkmark |

| Outcomes review: performance (including efficiency, effectiveness) |

4. Is there growth in online learning relative to in-person classroom learning? |

Addressed in the mid-point assessment |

| 5(a). Is there an increase in the number of registered learners |

Addressed in the mid-point assessment |

| 5(b). Is there an increase in learner satisfaction? |

|

checkmark |

checkmark |

|

|

| 6. Was a reduction in cost achieved? |

Addressed in the mid-point assessment |

| 7. Is the School's curriculum relevant to public servants and the Government of Canada? |

checkmark |

checkmark |

|

|

|

| 8. To what extent did Strategic Directions impact the overall range of learning products? |

checkmark |

checkmark |

|

|

|

| 9. Has the use of innovative technology been enhanced? |

Addressed in the mid-point assessment |

| 10. Has a common, core curriculum been established? |

checkmark |

checkmark |

|

|

|

| 11. Can the School provide evidence of the outcomes of training it delivers? |

checkmark |

checkmark |

checkmark |

|

|

| 12. Is there an increase in the level of knowledge acquired by learners and are they applying what they learn on the job? |

|

checkmark |

checkmark |

|

|

| 13. How can the School measure the outcomes of the evolving, learning ecosystem? |

|

checkmark |

|

checkmark |

|

3.3 Lines of evidence

Findings from 5 lines of evidence were synthesized to address each outcomes review and funding model review question.

Data collection methods included a document review (over 150 documents were reviewed, including internal School documents ranging from project plans to reports, as well as various tracking toolsNote 5) and the collection of related administrative data pertaining to product registrations and evaluations recorded by the School from 2013–14 through 2016–17. Interviews were conducted with 45 key informants (17 external senior interviewees, 18 additional external interviewees and 10 School intervieweesNote 6). Appendix B contains a list of interviewees, with identifiers removed to protect confidentiality. Finally, a literature review was conducted on methods to measure and report on the learning outcomes of the School's learning ecosystem. A review of the School's funding model was also conducted as a 5th line of evidence.

Data were compiled, analyzed, and synthesized by evaluation question using evidence matrixes, and presented in separate technical reports for each line of evidence. In the case of key informant interviews, the responses of internal and external interviewees were analyzed separately.Note 7 Analyses from separate evidence sources were triangulated to maximize the reliability and credibility of findings and conclusions. Recommendations are linked to findings and conclusions, and were reviewed by School officials to ensure that they were realistic and implementable. The School provided a corresponding management response.

4. Findings

4.1 Was the amount reallocated to the School aligned with the level of ongoing expenditures required to deliver the new business model (EQ2)?

The School's reference levels for the years following the transition period (2017–18 and beyond) appear to be aligned with projected expenditure requirements.

The funding model review determined that, because activities undertaken as part of SDI are still stabilizing and will continue to do so for at least 2 more years, and future demand is difficult to predict so early in the life span of the new funding model, it is premature to assess with certainty the future resource requirements of the School. That said, it would appear that current reference levels for 2017–18 and beyond will be sufficient in the near term, with the caveat that further augmentations in School responsibilities might need to be accompanied by additional funding.

Since its establishment in 2004,Note 8 the Canada School of Public Service operated through a combination of annual appropriations covering certain activities ($40 million to $60 million per year) and revenues from other activities ($25 million to $75 million per year). The Strategic Directions Initiative changed the School's funding model to one based primarily on appropriations. Departments and agencies comprising the core public serviceNote 9 were required to reallocate $230 per indeterminate and term employee (totalling $56.2 million) back to the treasury. Of this amount, $34.1 million (representing $140 per indeterminate and term employee) was added to the School's existing appropriation. In return, employees would be given unlimited access to GCcampus and all of the online resources available on the platform. Each department and agency would also be allocated a minimum number of seats in CSPS classroom-based learning activities in proportion to the size of the department or agency. The funding model change was phased in over the 3 years of the SDI period. As noted in Chapter 2, the School's expenditures in the most recent fiscal year, and final planned year of the Initiative, 2016–17, totalled $82,784,238.

4.2 Are the School's revenue and spending authorities appropriate (EQ3)? Should the School's statutory mandate and revenue and spending authorities be adjusted to reflect its new mandate and business model (EQ1)?

The School's revenue and spending authorities are appropriate and do not need adjustment.

While a detailed examination of the School's statutory mandate was beyond the scope of the evaluation,Note 10 an analysis of documentation provided by the School in combination with the funding model review enabled an assessment of the continued relevance of the School's spending authorities. Following the transition, the School retains authorities granted under sections 18(1) and 18(2)Note 11 of the Canada School of Public Service Act, including the authority to collect fees that are sufficient to recover costs, and to carry over revenues from these fees to the next fiscal year.

The School continues to collect fees from organizations covered by the CSPS's mandate that are partially or not funded through appropriations, and from those organizations with optional inclusion to the CSPS's services, at the fee of $230 per employee through interdepartmental settlements. Other requirements are that (a) the design, development and delivery of learning, either identified as a priority or requested by departments, meet the common learning needs of the public service over and above the existing and planned core common curriculum and that (b) the use of CSPS's facilities for fees is established through the Treasury Board's Guidelines on Costing (2016).

Flexibility associated with the authority to carry over revenues from fees to the next fiscal year is needed to accommodate the fact that planning, design, development, testing and delivery often extend beyond the annual planning cycle. Under the Canada School of Public Service Act, the School is permitted to set aside unspent revenue to ensure adequate funding for these activities into the next fiscal year.

These authorities are a requirement for the School to continue to efficiently and effectively implement the new business model with the assurance of adequate financial capacity and the ability to absorb changing priorities and demands year-to-year. Adjusting the authorities could limit the School's ability to provide, in particular, services to organizations outside of the core public service and services considered outside of the core common curriculum. Furthermore, the funding model review determined that in the near term these authorities do not pose a risk or other liability for the Government.

4.3 To what extent did Strategic Directions impact the overall range of learning products (EQ8)?

Under SDI the overall range of learning products changed substantially.

During the 3-year SDI period, substantial changes were made in the number, and available types, of learning products. As of the end of the 3-year SDI period, 68% of classroom and self-paced online learning products are new. The number of classroom-based, instructor-led learning products was reduced while the number of events and self-paced online learning products was increased. This conforms with direction given to the School at the outset of the Initiative to gain efficiencies and generate savings for the Government of Canada (while simultaneously increasing learning product accessibility) by shifting from a classroom-based to a predominantly online learning model.

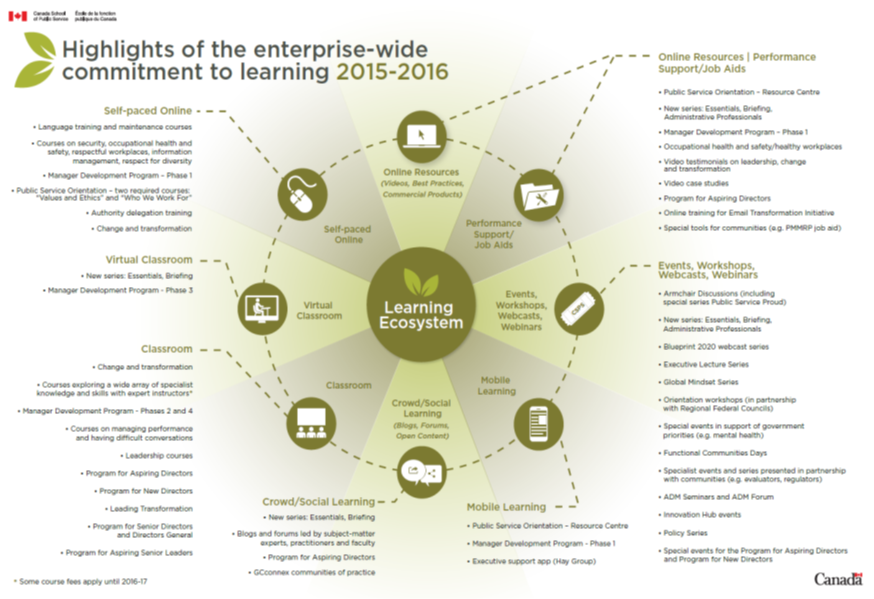

In the course of the Initiative, the School worked to develop learning products of 8 types. This collection of learning modes is known as the "Learning Ecosystem" (see following diagram). As shown in Table 3, the number of classroom-based, instructor-led learning products was reduced substantially from 262 in 2013–14 to 87 in August 2017. Instructor-led training hours were reduced from 787,266 in 2013–14 to 440,019 in 2016–17.Note 12 Self-paced online learning products increased from 188 to 243 during the same period, with much classroom learning content being transformed into online learning content. The number of virtual classroom products remained stable at 3. The number of events increased from 81 to 372 between 2014–15 and 2016–17. Increases for other categories of products cannot be computed because the School was not able to provide pre-SDI records for these categories. The number of mobile learning products is not tallied by the School; however, an examination of a randomly selected set of self-paced online products available on GCcampus suggests that mobile learning is an option offered for many online products. Not including unknown figures, the total number of products rose over the SDI period from 534 to 928, with the increase due mostly to increases in the number of events and online resources.

Text version of the Highlights of the enterprise-wide commitment to learning 2015-2016 image

The diagram depicts the School's learning ecosystem as a circle. Radiating outward from this central circle are the following 8 components of the learning ecosystem:

- online resources (videos, best practices, commercial products)

- performance support and job aids

- events, workshops, webcasts and webinars

- mobile learning

- crowd and social learning (blogs, forums, open content)

- classroom

- virtual classroom

- self-paced online

Each of these components is represented by a pictogram. The 8 pictograms are interconnected by a dotted line, which forms a large circle that orbits around the central learning ecosystem. Each pictogram points outside the circle to a list of the course offerings under that component.

Table 3. CSPS learning products in 2013–14 and 2016–17. Read down the first column for the learning products, then to the right for total learning products in 2013–2014, followed by total learning products in 2016–2017.

| Learning products |

2013–14Note 13 |

2016–17Note 14 |

| Classroom |

262 |

87 |

| Self-paced online |

188 |

243Note 15 |

| Events, workshops, webcasts, webinars |

81Note 16 |

372 |

| Crowd/social learning (blogs, forums, open content) |

unknown |

39 CSPS blogs |

| Online resources (videos, best practices, commercial products) |

unknown |

141 videos

2 case studies |

| Performance support/job aids |

unknown |

65 |

| Mobile learning |

unknown |

unknown |

| Virtual classroom |

3 |

3 |

| Total |

534 |

928 |

A total of 68% of today's CSPS curriculum is new, and many if not most topics previously offered through classroom courses are now offered through self-paced online products. As shown in Table 4, a more detailed analysis of classroom and self-paced online products revealed substantial changes; of a total of 450 classroom and self-paced online products, only 97 were retained. 195 classroom-based courses and 158 self-paced online courses were dropped. 20 new classroom-based courses were added, but the vast majority of new products (189) are self-paced online courses. A total of 67% of new self-paced online learning products were purchased from commercial training product suppliers Vubiz and SkillSoft.

Table 4. Changes in classroom and online products from 2013–14 to 2016–17. Read down the first column for the types of products offered (classroom or online), then to the right for the number of products offered in 2013–2014, the number of products removed, the number of products retained as is, the number of new products, and the number of products at the end of 2016–2017.

| |

2013–14 |

Removed |

Retained as is |

New |

At end of

2016–17 |

| Classroom |

262 |

195 |

67 |

20 |

87 |

| Online |

188 |

158 |

30 |

189Note a |

219Note b |

A detailed analysis of topics covered by School products was beyond the scope of the evaluation, and the School was unable to provide a list of topics cross-referenced by learning product.Note 17 Nevertheless, several broad observations can be made with respect to changes in learning topics. First, while the overall focus of the School has not fundamentally altered, there appears to be a greater emphasis now on learning related to organizational change and transformation. At the same time, as discussed in more detail in the next section, the School has attempted to shed offerings not determined to be part of what is considered to be the core common curriculum, while adding coverage in areas related to 14 identified priorities. For reference, the current topic list, taken from GCcampus in September 2017, is shown in Appendix C.

As part of the Initiative, a new committee, the School Content Integration Committee (SCIC), was formed to oversee changes in the range of learning products and the alignment of these products with the School's core mandate, priorities and capacity, and to provide ongoing coordination of future curriculum development. SCIC's aim is to ensure comprehensive coverage without undue overlap.

Department and agency representatives generally expressed an appreciation of the renewed range of learning products, recognizing that it is an ongoing process and reminding the School of the continued value of face-to-face learning in certain circumstances.

Interviewees based in departments and agencies generally felt the School is going in the right direction with a wider range of more easily accessible learning products. Appreciation was expressed for the ecosystem including no-cost, self-paced online learning activities; armchair discussions and other thematic events; WebEx-enabled events; and videos, blogs, etc. Some interviewees noted that the School is less "National-Capital-Region-centric" and travel burdens are reduced. Some external interviewees noted improved alignment between what the School offered and what their organizations required, enabling personnel in some departments and agencies to increase their engagement with the School and reduce their reliance on in-house training. In this way, increasingly the School can become the main "go-to" provider of learning opportunities for the federal public service.

Some departmental representatives expressed concerns about the School's increased reliance on online learning products. In-person modes are necessary for some kinds of learning, and making connections and building networks remains an important outcome of classroom-based programs. The shift to a greater reliance upon online products has also had the effect of reducing learning opportunities for employees with limited internet access, such as employees in remote locations or on ships, employees in highly restricted, secured IT environments, and blue-collar workers.

The reduction in classroom-based learning products also created apprehension with respect to the availability of space in classroom courses. Interviewed representatives of some departments were concerned that available classroom seat allocations may not be sufficient to meet their needs.

Curriculum transformation at CSPS is, and is expected to always be, ongoing, with learning products being revised and added in line with changing needs and priorities. External as well as School interviewees generally agreed that curriculum transformation was a work in progress. The Initiative accomplished a significant renewal, with most curriculum transformation objectives being achieved. The only major area where transformation is behind schedule is in specialized learning products (IM/IT, Communications, Finance, HR, Security, Procurement, and Policy), due primarily to the fact that the federal public service policy reset exercise, which is likely to alter significantly the content of learning products in this area, is still underway.

4.4 Has a common, core curriculum been established (EQ10)?

The School has successfully established a core common curriculum as identified by the CSPS Advisory Committee.

Although the Canada School of Public Service Act does not require the School to deliver a "common, core curriculum," nor is such a curriculum defined in the Act, the direction given to the School for the Initiative called for the School to put in place "core common training…to develop the knowledge, skills and competencies that are common to employees across the core public administration and unique to government."Note 18 Interviewed CSPS officials reported that the School interpreted this definition as referring to topics relating to the performance responsibilities of a critical mass of public servants, enterprise-wide, leaving to individual departments and agencies mandate-specific learning. CSPS officials also noted that the School considered learning priorities of the Government and the federal public service to be part of the definition.

During the transformation period, the School engaged in a considerable amount of consultation regarding core common learning needs with users and potential users of the School's products and services in federal departments and agencies;Note 19 in particular, senior officials were widely consulted, including key officials such as the Clerk of the Privy Council. CSPS analyses stemming from these consultations were reviewed by members of the Enterprise Editorial Board (made up of heads of learning from a range of client institutions) and members of the CSPS Advisory Committee (made up of deputy ministers). Consultations focused on identifying the topics to be considered as comprising the core common curriculum offered by the School, including learning priorities for the Government and the federal public service.

The consultations confirmed the need for learning related to common topics such as values and ethics, service to the public, public service management, and enabling functions such as financial services, human resources services, and security. The consultations also led to the generation of a list of 14 parallel learning priorities.Note 20 The learning priorities were seen as themes associated with an effective public service and meant to be interwoven with the common topics. Taken together, these topics and themes, as approved by the CSPS Advisory Committee, comprise the core common curriculum.

The renewal of the curriculum described in the preceding section aimed to put in place an adequate set of learning products associated with agreed-on common topics. In some cases there would be multiple products associated with a single topic, providing choice to the learner. During the 3-year SDI period, according to School officials, all priorities were incorporated as stand-alone products, or parts of products, comprising the School's curriculum. School officials noted that measures required to address the priorities varied widely. In some cases, according to School officials, a few one-time events were considered to be enough. In other cases, material related to a priority was dealt with more comprehensively. For example, Indigenous themes have been addressed through various events, and are also being incorporated comprehensively into key learning products as a permanent feature.

At the same time, some offerings were eliminated from the curriculum because they were considered not to be aligned with the definition of a core common curriculum. For example, the Retirement Planning series was dropped because retirement planning does not relate to public servant performance responsibilities, and training and other activities related to retirement planning are widely available in the private sector. Similarly, negotiation skills and team skills were seen as topics well served by the private sector, and consequently were dropped from the School curriculum. Offerings that have remained in the curriculum despite not being "unique to government" are included because they relate to priority themes. This is particularly true with respect to offerings related to change management and project management.Note 21

Department and agency officials generally appreciate the increased clarity that has accompanied the renewed curriculum, but still find limitations in the operationalization of the definition of "core common curriculum."

External interviewees expressed appreciation for the consultation process, and suggested that the result is a clearer, more focused core common curriculum. Interviewees spoke particularly highly of the renewed range of leadership programs along with the new Service Excellence suite of courses. Concerns were expressed by some external interviewees, however, with the fact that the core common curriculum was largely defined by the most senior officials in the federal public service, with little in the way of consultation with middle managers and front-line staff.Note 22

Some external interviewees, including senior external interviewees, also questioned what appeared to be a literal interpretation of the term "core common" as meaning that the subject matter must be of interest to employees in virtually every department and agency. For example, representatives of departments and agencies with large scientific complements, with large blue-collar complements focused on enforcement and security, or mainly on policy, suggested that their needs were distinct enough that they required tailored training in areas such as management and leadership. Following SDI, these departments and agencies find that they still need to provide training on their own because the School's programs do not meet their needs. Concern was expressed by some of these representatives who noted that, despite reallocating budget dollars to the School, they have not been able to correspondingly reduce their training budgets.

As noted above, curriculum development efforts are ongoing and will never be finished. During the 3-year SDI period, however, the bulk of the work was done to put in place learning products addressing the core common curriculum as defined by the School and its advisory committees, including identified priorities.

4.5 Is the School's curriculum relevant to public servants and the Government of Canada (EQ7)?

The School's curriculum, as of the end of the 3-year SDI period, was found to be relevant to public servants and the Government of Canada.

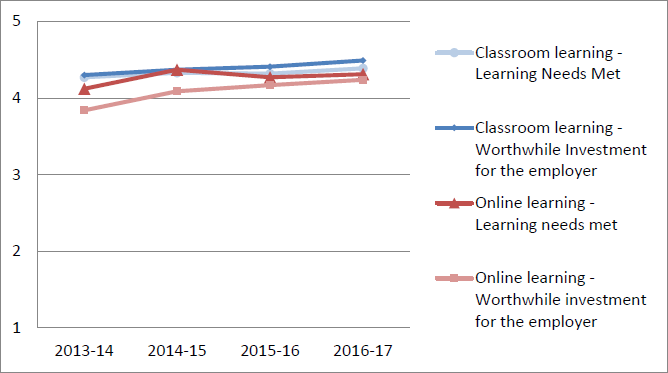

The School has, for years, surveyed learners immediately following the completion of learning activities with respect to their perceptions regarding various aspects of the activity. Figure 2 shows learners' responses on a 5-point scale to the "strongly agree-strongly disagree" survey items, "This learning activity met my learning needs" and "This learning activity was a worthwhile investment for my employer," averaged across all classroom-based and self-paced online learning activities from 2013–14 through 2016–17. As shown in the figure, learner perceptions regarding the extent to which learning activities met their learning needs for classroom-based learning products increased from 4.3 to 4.4 from the last pre-SDI year (2013–14) to the 3rd year of the SDI period (2016–17). For online learning products, learner perceptions regarding the extent to which learning activities met their learning needs increased from 4.1 to 4.3. During the same period, learner perceptions regarding the extent to which learning activities represented worthwhile investments for their employer for classroom-based learning products increased from 4.3 to 4.5. For online learning products, learner perceptions of the extent to which learning activities represented worthwhile investments for their employer increased from 3.8 to 4.2. These high numbers, which in all cases increased over the SDI period, suggest perceptions of relevance of School learning products.

Figure 2. Learning needs met and worthwhile investment (classroom and online)

Text version of the Learning needs met and worthwhile investment (classroom and online) graphic

Learning Needs Met and Worthwhile Investment. Learner perceptions, broken down by vote for strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), are presented in a line graph for fiscal years 2013–2014, 2014–2015, 2015–2016, and 2016–2017. The amounts are as follows:

Classroom learning needs were met

- 2013–2014: 4.27

- 2014–2015: 4.33

- 2015–2016: 4.22

- 2016–2017: 4.39

Classroom learning is a worthwhile investment for the employer

- 2013–2014: 4.27

- 2014–2015: 4.37

- 2015–2016: 4.41

- 2016–2017: 4.49

Online learning needs were met

- 2013–2014: 4.12

- 2014–2015: 4.37

- 2015–2016: 4.27

- 2016–2017: 4.31

Online learning is a worthwhile investment for the employer

- 2013–2014: 3.84

- 2014–2015: 4.09

- 2015–2016: 4.17

- 2016–2017: 4.24

Aside from the above, there is little by way of objective criteria against which to assess the relevance of the renewed CSPS curriculum. A systematic, comprehensive, enterprise-wide, assessment of public servant learning needs has not been conducted. Nor were standards such as internal benchmarks or textbook lists referenced. As noted earlier, the Canada School of Public Service Act does not specify a required curriculum. Modern federal public service vision and strategy-related documents, such as Blueprint 2020, Destination 2020, and the Clerk's annual reports on the public service to the Prime Minister, provide only general reference points without going into detail about learning topics.

Nevertheless, the majority of both internal and external interviewees stated that they perceived the renewed curriculum to be relevant, providing a degree of baseline knowledge. Some external interviewees, however, also questioned whether the approved core common curriculum is extensive enough, or touches on all of the right subjects. One senior external interviewee, for example, wondered if the core common curriculum for public servants should include learning opportunities related to critical thinking, analysis, and judgment.

4.6 Is there an increase in learner satisfaction (EQ5b)?

Learner satisfaction with self-paced online learning products increased over the 3-year SDI period. Satisfaction with other learning modes remained stable.

Table 5 shows overall satisfaction, taken from the immediate post-course learner survey, across all activities occurring in a single year, for the 3 main types of learning products, comparing pre-SDI levels with levels obtained in the final year of the Initiative. As can be seen in the table, levels increased marginally for classroom training and events, and somewhat more substantially for self-paced online learning products.

Although changes between the pre-SDI year and the final SDI year were in a positive direction, caution should be exerted in interpreting, in particular, event gains, because they were so small. On the other hand, gains and satisfaction scores for classroom-based, instructor-led learning products and, especially, self-paced online learning products, were notable and suggest that changes and enhancements made to the School's suite of self-paced online learning products appear to have contributed to higher levels of learner satisfaction with these products.

Table 5. Overall satisfaction with learning activities. Read down the first column for the type of learning product (classroom, online or events), then to the right for the learner satisfaction scores before the Strategic Directions Initiative (2013–2014 for classroom and online, 2014–2015 for events), followed by the learner satisfaction scores after the launch of the Strategic Directions Initiative (2016–2017).

| |

Mean learner satisfaction scores

(out of 5 on the agree-disagree item:

“Overall, I was satisfied with this learning activity”) |

Pre-SDI (2013–14 for classroom and

online, 2014–15 for eventsNote 23) |

Post-SDI Launch (2016–17) |

| Classroom |

4.49

(respondents = 20,210, response rate = 47.1%) |

4.58

(respondents = 11,097, response rate = 44.3%) |

| Online |

4.01

(respondents = 23,692Note 24) |

4.34

(respondents = 24,981) |

| Events |

3.96

(events = 52, respondents = 3,133) |

4.04

(events = 83, respondents = 6,376) |

Most interviewees, both within and outside the School, felt that learner satisfaction is an important concept to measure; satisfaction is an indicator that, at a minimum, the learner experience with CSPS products was good, suggesting that learners will be encouraged to continue to seek learning opportunities at the School. Some external and School interviewees suggested that high satisfaction with self-paced online learning products may reflect shifting learning preferences (greater acceptance of this mode as the "default" mode of learning). Some external interviewees reported that high satisfaction scores help enable them to more confidently recommend the School to their employees.

4.7 Is there an increase in the level of knowledge acquired by learners, and are they applying what they learn on the job (EQ12)?

Limited School research revealed learner knowledge gains and positive impacts on learner job effectiveness following some learning activities, but these observations are not generalizable to the range of School products.

The School uses the Kirkpatrick modelNote 25 in describing learning evaluations: Level 1 refers to learner reactions, including satisfaction, immediately following the learning activity; Level 2 refers to learning, or knowledge/skill acquisition; Level 3 refers to resulting behaviour changes, or the on-the-job application of newly acquired knowledge or skills; and Level 4 refers to results, typically in the form of organizational improvements stemming from application.

As noted earlier, the School regularly assesses and reports on learner satisfaction. Immediately following a learning activity, registered learners are automatically sent an online questionnaire that includes questions on satisfaction (Level 1). The questionnaire also includes learner perception questions related to Levels 2 and 3: "Please rate your level of knowledge in the subject area before and after the learning activity" (Level 2); and "I am motivated to apply this learning on the job," "I am confident in my ability to apply this learning on the job," and "My work environment will allow me to apply what I have learned" (Level 3). However, the evaluation found no evidence that data stemming from these Level 2 and Level 3 items are analyzed and systematically reported to audiences outside of the School.

Reporting on Level 2 and 3 results is limited to a small number of learning activities each year and thus is not generalizable to the full range of School learning products. Rather than relying on learner perceptions, for selected coursesNote 26 "knowledge" is determined through knowledge testing. Identical tests are given to learners before and after the learning activity. Knowledge gain is the percentage difference between pre- and post-course scores. Knowledge gain was measured for 8 courses in 2013–14Note 27 and for 12 different courses in 2015–16.Note 28 (Knowledge gain data for 2016–17 were not collected.) In 2013–14, knowledge gain scores ranged from 12% to 78%. In 2015–16, knowledge gain scores ranged from 6% to 129%. A valid comparison between the 2 periods is not possible because different learning products were examined.

Respecting Level 3 evaluation, the on-the-job application of newly learned skills and knowledge (sometimes referred to as "learning transfer") is also specially measured by the School for selected courses and programs each year.Note 29 In 2013–14, participants from 6 learning activitiesNote 30 received online Level 3 surveys. In 2014–15 through 2016–17, participants from 4,Note 31 20,Note 32 and 7Note 33 learning activities, respectively, received online Level 3 surveys. Online surveys were sent to learners, and in some cases, learners' immediate supervisors, 3 to 6 months after the learning activity. In the 2013–14 survey, 2 questions were asked relating to (i) behaviour change following participation in the learning activity, and (ii) the learning activity's impact on the learner's effectiveness at work. Starting with the 2014–15 survey, different Level 3 questions were asked relating to "use [of] new knowledge, skills and attitudes learned during the course," and workplace support received for the application of new knowledge. The 2013–14 question relating to effectiveness was retained. In 2015–16 and 2016–17, the same questions were used. In addition, for 1 learning activity in 2015–16Note 34 and 3 learning activities in 2016–17,Note 35 learners' supervisors were surveyed and asked to rate their level of agreement or disagreement with the statement, "the Program helped improve my employee's performance."

Table 6 shows application metrics for the 7 learning activities examined in 2016–17. As can be seen, a majority of respondents used the knowledge, skills or attitudes learned during the learning activity they took part in. Most respondents also received support in their workplace for knowledge application and reported that the learning activity positively impacted their work performance. Most supervisors who provided feedback either agreed or strongly agreed that the program had improved the employee's performance.

Table 6. Level 3, knowledge application (2016–2017) in percentage. Read down the first column for the courses, then to the right for the response rates, followed by the percentages of respondents who agreed or strongly areed with the statements about knowledge application under the following categories: use of new knowledge, skills, and attitudes; workplace support; effectiveness improvement; and supervisor perception of impact on employee.

| Course |

Response rate |

Use of new

knowledge,

skills and attitude

(respondents

who agreed or

strongly agreed)

|

Workplace

support

(respondents

who agreed or

strongly agreed)

|

Effectiveness

improvement

(respondents

who agreed or

strongly agreed)

|

Supervisor

perception of

impact on

employee

(respondents

who agreed or

strongly agreed)

|

| T198 |

294/715 – 41% |

97% |

84% |

82% |

N/A |

| T718 |

78/178 – 44% |

73% |

67% |

78% |

N/A |

| T233 (online) |

148/529 (sampling) |

92% |

87% |

64% |

N/A |

| SDP |

346/707 – 49% |

93% |

86% |

81% |

N/A |

| MDP |

PNote 36: 386/645 – 60% |

98% |

85% |

86% |

74% |

| S: 225/473 – 48% |

| ADP |

P: 249/463 – 54% |

98% |

90% |

75% |

73% |

| S: 244/430 – 57% |

| NDP |

P: 106/200 – 53% |

98% |

86% |

87% |

74% |

| S: 85/170 – 50% |

Because of changes in survey questions and analysis and reporting protocolsNote 37 from year to year, and the fact that different learning activities were subjected to a Level 3 evaluation each year, a valid comparison between pre-SDI performance and performance in the last year of the 3-year SDI period is not possible. The School developed internal reports each year facilitating a comparison of application metrics across learning activities within a given year. For example, in 2015–16, mean learner perceptions respecting the impact of the learning activity on their effectiveness ranged from a low of 20% of respondents indicating "significantly" or "greatly" (Course I104) to a high of 82% for the Manager Development Program (MDP).

4.8 Can the School provide evidence of the outcomes of training it delivers (EQ11)?

As a result of the activities undertaken as part of the Initiative, the School has in place an upgraded business intelligence system that, combined with existing data collection practices, is capable of providing a comprehensive range of outcome metrics.

A significant aspect of the Strategic Directions Initiative involved an extensive upgrade of the School's business intelligence systems, which the School continues to refine. The result to date is an integrated platform able to combine, and report in a wide variety of ways on, data from the School's learning activity registration system, GCcampus, learning activity evaluations, and federal public service "master lists" containing information on departments, regions, locations, and priorities.

School officials generally agree on the quality and usefulness of internal reports and dashboards generated by the new platform. The evaluation examined numerous sample reports and dashboards, noting the range available and the flexibility of the system to easily generate additional reports containing virtually any combination of metrics.

The system is limited only by the data to which it has access. Notable gaps in this regard include the kind of rigorous Level 2 and Level 3 evaluation data mentioned in the preceding section,Note 38 and course completion data. With respect to the latter, the system can report on registrations but cannot always determine whether or not a registrant completes the learning activity. Particularly with respect to self-paced and other online learning products, information about a registration does not equate with confirmation that the learner undertook and completed the learning associated with the product.Note 39

Various iterations of external report models have yet to satisfy the needs of client departments and agencies.

External interviewees at all levels noted the lack of information on learning and application related to the School's learning products, and School informants recognized this deficiency. School representatives report that progress is being made on this front and, in future, Level 2 and Level 3 evaluations will be conducted and reported on with greater frequency. Department and agency representatives would reportedly welcome such a development suggesting that Level 2 and Level 3 data should be collected with essentially the same regularity and through the same means as the current Level 1 process.

According to external interviewees, an early expected output of the Initiative, and one highly anticipated by departments and agencies (as noted in the formative evaluation) was the generation of regular activity and outcome reports. As part of the transformation associated with the Initiative, and in light of the reallocation of budget dollars from departments and agencies to the School, departmental officials were hoping for frequent feedback respecting usage of School resources and engagement in School activities on the part of their employees, and the impacts of this usage and engagement on employee performance. In practical terms, deputy heads (who are ultimately accountable for employee learning in their organizations) and heads of learning wanted regular updates on the learning activities and products being used by their employees; an indication of remaining classroom seat allocations for the year; and learning evaluation metrics (especially at Levels 2 and 3) for their employees, by learning activity.

In the early part of the 3-year Initiative period, the School was unable to meet department and agency demand for feedback, largely because the upgrade of the School's business intelligence systems was not complete. Departments and agencies received their first reports in December 2015. A second round of reports, now called the Learning Indicator Report, was sent to departments and agencies in June 2017.Note 40 The latest iteration reported on 4 performance indicators (reach, learner experience, repeat rate, and priority coverageNote 41) along with operational data (main learning activities, registrations, unique registrations for leadership programs, and regional distribution). Operational information was presented for each organization in comparison with the whole of the federal public service and with similar size organizations.

Interviewees representing departments and agencies voiced appreciation for the School's reporting efforts and were positive about elements of the report such as comparisons with similar size organizations and trends over time. However, generally speaking, interviewees based in departments and agencies expressed disappointment in the reports themselves. They noted that they are not receiving in these reports the information they desire; department and agency officials want monthly usage figures including information on completions and cancellations, and learning outcome metrics for their employees including statistical information such as response rates. Interviewed department and agency representatives were also critical of report formats, finding them difficult to digest and make use of. For their part, School officials point to the diversity of department and agency models and reporting desires as hindering the generation of standardized reports.

At the same time that the School generated standard reports, it also responded to individual department and agency requests for customized reports.Note 42 For example, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) asked for and received Level 1 and Level 3 evaluation figures for its employees who attended MDP during 2016–17 in comparison with MDP attendees from across the federal public service. The CRA was satisfied with the reports it received. Other departments and agencies have had similarly positive experiences with requests for customized reports, although still other departments and agencies report dissatisfaction with the School's responses to their requests for customized reports. Department and agency representatives also have direct, limited access to School databases from which they may extract their own data and reports. Interviewees with experience with the databases report limited success and satisfaction.

4.9 How can the School measure the outcomes of the evolving learning ecosystem (EQ13)?

A system that appropriately and effectively measures the outcomes of the School's evolving learning ecosystem will need to go beyond traditional learning evaluation concepts and data collection approaches.

The Kirkpatrick model applies effectively to learning and behaviour stemming directly from formal learning activities.Note 43 Common estimates suggest that this learning represents roughly 10% of an employee's overall learning, with 20% stemming from informal learning and mentoring, and the remaining 70% stemming from work experience. All learning can be affected by the supportiveness of the learner's environment and by learner motivation.

The expansion of the range of learning modes, particularly toward increased involvement of less structured, self-paced learning modes accessed online and through mobile devices, also affects possibilities and requirements associated with a potential outcomes measurement system. Learning products that do not require registration are not amenable to survey methodologies that require an email address. Learners consuming learning in short bursts, in a piecemeal fashion, or via online "grazing," are unlikely to respond to formal requests for feedback in relation to these episodes. Indeed, learners may not even characterize some of this activity as "learning," even in cases where it was provided by the School or stimulated by School activities.

The School lacks a comprehensive, strategic model by which methodologies are adopted in line with evaluation needs which themselves are determined by the anticipated needs of decision-makers.

If the School's ecosystem continues to incorporate an increasing amount of informal learning opportunities, while at the same time seeking to more broadly foster a learning culture that stimulates an appetite for further learning, a detailed, comprehensive outcomes measurement and evaluation system will need to be developed including metrics that go beyond the standard reaction, learning, behaviour, and results associated with Kirkpatrick. The menu of methodologies will need to be expanded to include approaches such as the following:

- automatedNote 44 online surveys

- live, post-course feedback sessions with learners

- in-class or online learning activity features such as quizzes, demonstrations and observations, role-plays, and peer teaching

- pre- and post-event job performance comparisons

- learner interviews

- learner case studies

- web analytics examining page views, engagement metrics, etc.

- pop-up surveys built into mobile learning products

- social media activity tracking

- other technology-driven solutions

Curriculum developers need high-quality evidence with respect to the learning needs and preferences of the target audience in order to continuously enhance the relevance of the curriculum and specify learning objectives. Designers need evidence related to product features (what works, and what does not?) in order to improve learning products. School executives and federal public service leaders need evidence of the value of the School's learning activities to support expenditure decisions.

The expanding range of measurement questions and methodologies, combined with a broad array of different needs with respect to evidence, warrants in future a selective and strategic approach to the measurement of learning outcomes related to the School's ecosystem. It is neither practical nor necessary to measure everything. While a substantial new learning product such as the Manager Development Program warrants a comprehensive evaluation effort, a one-time, one-hour webcast on a topic of current interest probably does not. Every potential measurement task should begin with an assessment of decision-maker needs followed by a determination of the evidence that can best meet those needs within available resources. Practical measurement solutions, drawn from the full range of modern methodological options, should follow from these determinations.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

5.1 The new CSPS funding model has been successfully adopted, and planned reference levels and spending authorities appear to be appropriate

Because activities undertaken as part of SDI are still stabilizing and will continue to do so for at least 2 more years, and future demand is difficult to predict so early in the life span of the new model, it is premature to assess with certainty the future resource requirements of the School. That said, it would appear that current reference levels for 2017–18 and beyond will be sufficient in the near term, with the caveat that further augmentations in School responsibilities might need to be accompanied by additional funding.

Retaining the authority to collect fees and to carry over revenues from these fees to the next fiscal year, provides an appropriate level of flexibility for the School to efficiently and effectively implement the new business model.

Recommendation 1. It is recommended that, in future, estimated costs associated with the development and delivery of learning become a distinct element of consideration in Treasury Board submissions and Cabinet requests.

5.2 The School has established a relevant core common curriculum, as defined by senior officials

The School made substantial progress toward the establishment of a relevant core common curriculum. The School's focus is seen to have been sharpened, and department and agency representatives have greater confidence that the School can meet basic learning needs, leaving to departments and agencies mandate-specific training.

The core common curriculum is defined, in essence, as the topics and priorities deemed to be relevant to the performance responsibilities of a critical mass of public servants enterprise-wide, along with priorities identified at senior levels. The definition has not been systematically validated at the front-line level, however. Also, the idea of learner needs having to be "enterprise-wide" appears to have precluded training for significant subpopulations; officials in some departments and agencies believe their employees' needs fall largely outside the purview of the School's new definition, and are left having to provide required training themselves.

Recommendation 2. It is recommended that the School, in consultation with senior officials as well as middle managers and front-line staff across all regions, continues to clarify, validate and refine the definition of its core common curriculum.

5.3 The School's range of learning products was extensively overhauled, improving accessibility and choice among learning modes

Under SDI the range of CSPS learning products changed substantially. The number of classroom courses fell from 262 to 87 while the number of events increased nearly fivefold to 372. The number of self-paced online learning products remained relatively stable (at 219 as of the end of 2016–17), but almost all were replaced with newer versions. In addition, new types of learning products were made available.

Department and agency representatives are generally positive respecting the renewed range of learning products, noting significant improvements in terms of learning mode choice and in the accessibility of learning opportunities. The School appears better able to respond rapidly to emergent priorities. Concerns remain, however, related to the shift from a model emphasizing classroom-based training to one relying more on online learning activities. Fewer classroom options can lead to perceptions among users about possible seat shortages. Also, an overreliance on online modes can impede training for employees without ready access to the internet.

Recommendation 3. It is recommended that the School continues to develop and optimize the range of learning modes associated with its learning ecosystem.

5.4 The School has yet to establish a robust outcomes measurement regime

CSPS has collected Level 1 evaluation data since long before SDI, and found through its Level 1 data tracking efforts that satisfaction with self-paced online learning products increased over the SDI period. Level 1 observations are, however, of the least interest to department and agency representatives who are keener to know the extent to which their employees are acquiring new knowledge and skills from their School experiences and the extent to which they are applying these learnings on the job.

The School collects elementary knowledge acquisition and learning application data on most activities for which registration is required, plus detailed data on a small sample of learning activities each year, but it has not developed an analysis protocol sufficient to satisfy client organizations. Moreover, in light of the evolution of the School's learning ecosystem, a system that appropriately and effectively measures learning outcomes will need to go beyond traditional evaluation concepts (the Kirkpatrick model) and traditional evaluation data collection approaches. Departments and agencies must be involved in data collection. In short, a more comprehensive and strategic approach is required to meet the demands of departments and agencies, as well as the needs of the School, by which methodologies are adopted in line with evaluation needs.

Recommendation 4. It is recommended that the School builds upon existing learning evaluation practices, and invests appropriately to create a comprehensive evaluation regime capable of collecting, analyzing, and reporting on data in relation to satisfaction, learning, application and other concepts according to the needs of users.

5.5 SDI has given the School an upgraded business intelligence system capable of generating a wide range of reports; internal reports have been well received, however, client organizations remain unsatisfied

As a result of the activities undertaken as part of the Initiative, the School has invested in an upgraded business intelligence system that, combined with existing data collection practices, is capable of providing a wide range of outcome metrics. School officials are generally satisfied with reports generated for internal use. Various iterations of external report models, however, have yet to fully satisfy the needs of client departments and agencies. Department and agency officials want monthly usage figures, information on completions and cancellations, and learning outcome metrics for their employees including statistical information such as response rates.

Recommendation 5. It is recommended that the School improve its external reporting by establishing a system that generates reports that meet client requirements in terms of frequency, content, and format.

6. Management response and action plan

Management response and action plan. Read down the first column for the recommendation number (from 5.1 to 5.5), then to the right for the recommendation, followed by the management response, the actions to be taken, the timelines, and the offices of primary interest.

| No. |

Recommendation |

Management response |

Actions |

Timelines |

OPI |

| 5.1 |

It is recommended that, in future, estimated costs associated with the development and delivery of learning become a distinct element of consideration in Treasury Board submissions and Cabinet requests. |

Agreed.

CSPS will work with TBS to address this recommendation.

|